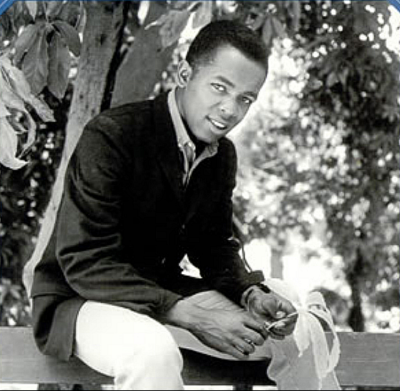

When the velvet-voiced crooner, Lou Rawls, sang a song, his smooth vocal stylings were immediately recognizable. The late performer Frank Sinatra summed up the soul, jazz, and blues vocalist with the four-octave range best when he once said, “Lou had the classiest singing and silkiest chops in the singing game.”

Lou also had crossover appeal, so his vocal gift was lauded by both Black and white audiences. The commanding baritone who exuded sophistication had a celebrated career as a recording artist with more than 70 albums, three Grammy Awards, 13 Grammy nominations, one platinum album, five gold albums, and a gold single.

Born Louis Allan Rawls on December 1, 1935, he was raised by his paternal grandmother on the south side of Chicago. Lou’s grandmother, who attended a baptist church, introduced him to singing at age 7. He listened to popular music as a teenager and loved frequenting shows at Chicago’s famed Regal Theater that played host to numerous famous African-American performers like Joe Williams, Arthur Prysock, and Billy Eckstine.

Lou decided to embark on a career as a singer and eventually joined The Teenage Kings of Harmony with his school friend Sam Cooke, who was four years his senior. Sam took on the role of Lou’s mentor and friend until his untimely death at age 33.

In ‘50, Lou made his recording debut with the Holy Wonders on Move In the Room. In 1951, he replaced Cooke as a singer with the gospel group Highway QCs. The group members sang in the tradition of jubilee quartets and helped to launch the singing careers of several secular stars, including Lou, Johnny Taylor, and Sam Cooke.

Lou joined The Chosen Gospel Singers in 1953. The group earned a reputation as being one of the most elusive of gospel’s golden era because constant lineup changes plagued them. Lou was one of their most famous alumni.

Lou took a break from his singing career in ‘56 to enlist as a paratrooper in the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division. After his military discharge two years later, Lou briefly joined another gospel group, the Pilgrim Travelers, along with Cooke. In November of ’58 in St. Louis, Lou, Cooke, and their driver Eddie Cunningham collided with a truck. The driver was killed.

Cooke sustained only minor injuries from the crash. Lou, on the other hand, ended up in a coma from a brain concussion for five days and was even pronounced dead. He suffered a three-month memory loss after the accident, and it took a year to recover from it fully. In later interviews, Lou described his brush with death as a life-changing experience.

After recovering from the accident that sidelined him for a year, Lou began performing secular music in small venues around the city. Lou was that stellar voice which shouted out the background “yeahs” on Cooke’s ‘62 classic Bring It On Home To Me. That same year, Lou released his debut album, the jazzy Stormy Monday, with the Les McCann Trio and landed his first acting role in the television series 77 Sunset Strip. (Lou had many minor parts in 18 films such as Leaving Las Vegas, appeared in numerous TV series, and had a sideline lending his baritone voice to cartoons such as Hey Arnold! and Garfield.)

Music historians often credit Lou as one of the first rappers with his unique storytelling style of inserting spoken narrative into songs like Tobacco Road, and he came into his own as a soul singer, with timeless hits such as Love Is a Hurtin’ Thing and the Grammy-winning Dead End Street. He won the second of his three Grammys for his 1971 socially conscious song Natural Man.

By the time the ‘70s rolled around, Lou jumped on the then successful Philadelphia International bandwagon and began working with hit makers such as the producer/songwriting team of Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. In 1976, the Philly team created the biggest hit of Lou’s career, You’ll Never Find, a ballad with a disco rhythm. The single sold a million copies and reached No. 1 on the Billboard R&B charts. The team then cranked out a successful array of disco-era hits, including Lady Love and Groovy People. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, Lou worked as a national pitchman for Budweiser and starred in Smoky Joe’s Cafe on Broadway.

Lou began his most crucial humanitarian endeavor explicitly aimed at the Black community, The Lou Rawls Parade of Stars Telethon, a yearly television event he would host for 25 years until his passing. Lou, who never attended college, was passionate about Black children getting a college education, and his tireless efforts raised nearly $350 million for the United Negro College Fund.

Lou basically lived a drama-free life compared to many of his celeb peers except for a couple of media-moments.

In 2003, Margaret Schaffer admitted to giving up her business to become Lou Rawls’ mistress and sued the soul singer for $12 million, claiming he backed out of a verbal agreement to support her financially for a lifetime even if they split.

After a courtship, when the 67-year-old singer admitted he was married, Schaffer said, she left her job with a fruit-brokerage business and moved into his Southern California home. They made an oral agreement in November 1998 “to treat as joint property income and earnings,” according to the lawsuit. A year after the filing, Lou finally agreed to pay Schaffer $35,000 to settle her $12 million lawsuit. Lou’s manager at the time, David Brokaw, who referred to the claim as a “nuisance” lawsuit, affirmed that while his client was acquainted with the woman, the two had never dated.

In 2004, Lou married his third wife, 33-year-old Nina Inman Rawls, a flight attendant, and they even adopted an infant son. Less than two years later, Lou filed for an annulment. The crooner claimed in court papers that Nina had wed him with the intent of taking his assets which he insisted, made the marriage invalid in the first place.

In her own affidavit, Nina said her husband had reportedly been “physically abusive” to her during the marriage. Even before they were wed, she said, he was arrested in New Mexico on abuse charges. Nina also claimed Lou had broken her cheekbone, wrist, and also hit her on the head with a knife sharpener. According to court papers, Nina declared, “I loved Lou and did not want him to go to prison, so I never cooperated with the prosecution.”

In a court filing, Lou’s lawyers alleged that his wife “exploited” his illness and “converted a large amount of Mr. Rawls’ assets for her own personal use.”

Lou died on January 6, 2006, at age 72, two months before the trial. Nina was by his bedside when he passed.

Besides his wife Nina and their son, Lou was survived by his three other children.