Growing up, I had a few favorite movie musicals like The Sound of Music, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, and Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.

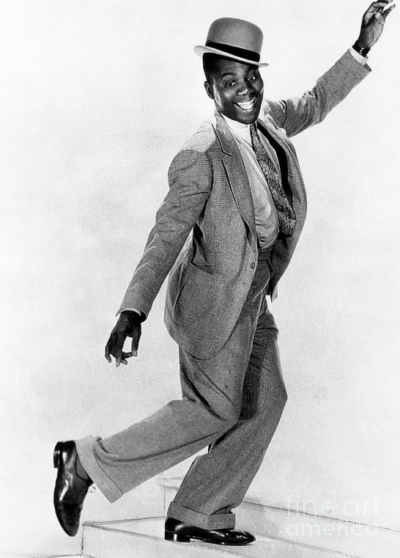

I also loved Shirley Temple films. One famous dance scene with Shirley stands out in my mind from the movie The Little Colonel. Shirley was a cute, dimpled, curly-haired, and precocious little girl. In the film, she is seen dancing up and down some stairs with her Black butler, portrayed by Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Bill is referred to as ‘the grandfather of tap dance’ and was the most famous and highly paid African-American entertainer in the first half of the 20th century.

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson was born Luther Robinson on May 25, 1878, in Richmond, Virginia. Bill’s parents Maxwell, a machinist, and Maria, a church choir singer, passed away when he was seven. There are no records of how the Robinsons died, but it is assumed they were killed together in an accident. Now an orphan, he and his younger brother, Bill, were sent to live with their grandmother, Bedilia, who had been a slave and did not want to raise small children. She was a strict Baptist who forbade dancing, gambling, and swearing in her presence.

Bill, who hated the name Luther, beat up his brother and took his name. The youngster rebelled against his strict grandmother and began hanging out on street corners and picking up tap lessons from other local Richmond youths.

By age five, Bill was dancing on the street and passing around a hat to collect pennies. He also danced at various public places and, two years later, dropped out of school. During this period, Bill began to refer to himself as “Bojangles” jokingly and use a term he coined–“copasetic”–that eventually found its way into the dictionary.

Bill’s big break came at age 9; he joined a traveling company, the Mayme Remington troupe based in Washington D.C., where he performed as a “pick” or “pickaninny” in the chorus. Pickaninnies were popular in minstrel shows. The term was a derogatory label used to describe and stereotype a dark-skinned Black child.

Even though being a stage performer was on his radar, Bill had difficulty finding work. So, at age 20, he returned to Richmond and joined the U.S. Army as a rifleman during the Spanish American War. Unfortunately, two years after enlisting, he was discharged after being accidentally shot.

The early 1900s introduced a new entertainment medium known as vaudeville. Blackface was still popular at the time and even expected of white and Black artists as well. Bill used his popularity to challenge racial barriers, including becoming one of the first minstrel and Vaudeville performers to appear without blackface makeup.

There was a “two-colored” Vaudeville rule that prevented Black performers from appearing alone onstage. Because of these restrictions, from 1902 until 1914, Bill was required to have an onstage partner. As a result, he danced almost exclusively in Black theaters for Black audiences. But, during this time, he pioneered a new form of tap-dancing. Bill’s dance style was elegant, quick and left his audiences awestruck. Bill also never used metal taps on his shoes. Instead, he danced a lifetime in shoes with wooden soles, wearing out as many as 30 pairs per year.

In 1908 while in Chicago, Bill met with his lifelong manager, who helped forge a business relationship between his client and dancer, George W. Cooper. The duo performed at various nightclubs, and their techniques were riveting; they even managed to cross the lines of segregation by performing in both Black and white establishments.

Later in 1908, after a dispute with a tailor over a suit, Bill was arrested in New York City. He was convicted and sentenced to 11–15 years of hard labor at Sing Sing, the infamous NYC prison. Unfortunately, Bill failed to take the charges and trial seriously and paid little attention to mounting a defense. After his conviction, Cooper organized his most influential friends to vouch for him and hired a new attorney who produced evidence that Bill had been falsely accused, though he was exonerated.

By World War I, Bill and Cooper parted company.

In 1918, Bill became one of the few Black performers to headline a show at the prestigious Palace Theater in New York. At that show, he introduced his most masterful exhibition of primo showmanship, the “stair dance,” where he danced up and down a staircase wowing his audiences. At one point, Bill was raking in about $3,500 per week for his performances.

Bill only appeared in two full-length feature films between 1930 and 1935-Dixiana and Harlem Is Heaven. In 1934, however, producers at Twentieth Century-Fox decided they needed a new partner for their biggest star, Shirley Temple. Although only seven years old, Temple had been featured in dozens of movies and was the industry’s biggest box-office draw every year between 1935 and 1938.

In their first film, The Little Colonel, Bill and Temple stair danced together, and their onscreen chemistry was fire. The pair were also film history’s first interracial dancing couple-and few have followed in their footsteps even today. Even though Bill portrayed the quintessential Uncle Tom in the film, his appearance with Temple was a giant step for Blacks in Hollywood. Bill and Temple made four films together.

Bill’s career had basically peaked in the late 30s. But in 1943, however, he got tapped to appear in the film Stormy Weather, co-starring the gorgeous Lena Horne. The all-Black musical was chockful of cream-of-the-crop talent–Fats Waller, Dooley Wilson, Cab Calloway, and Katherine Dunham.

Earlier Black entertainers were often looked upon as coons for furthering racial stereotypes on the big screen. Yet privately, many of these performers were not complacent when it came to race relations. Though Bill made millions over the course of his career, he gave away vast amounts to Black charities in Harlem, where he lived.

In one year alone, Bill performed in four hundred benefits. He was a founding member of the Negro Actors Guild of America. The performer even co-founded a Negro League baseball team, the New York Black Yankees. While visiting Richmond in 1931, he joined Maggie Walker’s Independent Order of St. Luke. In 1933, he witnessed Black children attempting a dangerous intersection in the Jackson Ward section of Richmond to get to school. He contacted the city and paid all costs to install a set of traffic lights at the intersection. For this act of charity, Richmond would later get its first monument to a Black citizen, in 1973, in Bill’s honor at that intersection.

On a personal note, Bill was an avid gambler with a bad temper who loved to play pool. He was married three times. In 1922, he married Fannie Clay, who became his business manager and secretary; the marriage was his second. In 1907, he had married Lena Chase, from whom he was divorced in 1922. Finally, after twenty-one years, he divorced Fannie and married a young dancer, Elaine Plaines. After three walks down the aisle, the marriages never produced children.

In 1970, the late showman extraordinaire, Sammy Davis, Jr., recorded the hit song, Mr. Bojangles. Many people assumed that the song was about Bill “Bojangles” Robinson when it wasn’t. Country singer Jerry Jeff Walker wrote the song about an old man he met while in jail. The inmate refused to give Walker his real name and instead just referred to himself as Mr. Bojangles, thus the song’s title.

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson died on November 25, 1949, at 71; the cause of death was heart failure. Although he died penniless after earning an excess of 4 million dollars during his 50-year career, his estate was probated at less than $25,000. Bill’s funeral was paid for by his friend television personality Ed Sullivan. He was given the biggest funeral Harlem had ever seen, with over 32,000 fans paying their respects. Honorary pallbearers included Sullivan and the great musical composer Irving Berlin. Harlem schools closed for half-day to listen to Bill’s service on the radio from Abyssinian Baptist Church which the Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. officiated.

The late actress Rosetta LeNoir, who portrayed grandma Estelle Winslow in the long-running sitcom Family Matters, was Bill’s goddaughter. LeNoire suffered from rickets as a young girl, which her godfather helped her overcome by teaching her to dance. In a prelude included in the book Mr. Bojangles: The Biography of Bill Robinson by James Haskins, LeNoir writes of her beloved godfather:

“Uncle Bob, you have always been and always will be one of the most accomplished, creative, famous, and talented dancers. Your generosity to everyone, regardless of sex, race, creed, or color, will never be topped. I mean that in the full sense of the word. You just loved people. Your generosity on all levels to everyone will never be topped.”