The gift of a long life is only a gift if it’s a life you’re fine with living. After all, it’s your life, and you should be able to decide whether it’s good. For most of us, however, the decision of when to die is not left to us, even if we make our wishes known. Instead, we children are left to decide the fates of our parents. The gift my mother gave me was a roadmap.

In the 70s, my mother would host intellectual salons for Black revolutionary thinkers. I sat on the stairs, just out of sight, listening, hoping to sneak some onion dip from the supply in the kitchen or maybe hear a juicy tidbit about the Black Panthers. Rumaki in one hand and a cigarette in the other, she’d sashay about the room in her I. Magnin hostess dress, provoking thoughtful discussion and offering up hors d’oeuvres. If the discussion turned to dying, she’d tell the room someone had better put a bullet in her head, because it was no life living in an old folks home. She repeated this whenever cancer, stroke, or dementia took a family member or friend.

Finally, in the early 2000s, we completed the legal advanced directives to make sure if anything happened to my mother, I would fulfill her long-voiced wishes. No heroics. Do not resuscitate. Pull the plug, she said.

Recently, I reread Ezekiel Samuel’s 2014 opinion piece in The Atlantic about his wish to die at 75. Noting he likely wouldn’t get his wish (he was too healthy) and further noting that this perspective drove his friends and family crazy because they wanted him around longer. Ezekiel was nevertheless resolved that 75 for him was enough time on this earth. Acknowledging that losing a parent is certainly a loss, he also noted, “living too long is also a loss. It renders many of us if not disabled, then faltering, and declining, a state that may not be worse than death but is nonetheless deprived. It robs us of our creativity and ability to contribute to work, society, the world.” My mother would have disagreed with only one thing: living too long is, in fact, worse than death.

After a series of fender benders, multiple cooking accidents, unusual emotional outbursts, and a few bizarre memory lapses in 2010, I asked – for my mother’s safety — that her doctor revoke her driver’s license, and I moved a caregiver into her house. Over the next year, it was clear her problems were more than just age-related dementia; she had Alzheimer’s. My mother could no longer manage her money or her life, even with a caregiver.

In 2011, my mother had already forgotten her advanced directive and was certain she had the intellectual stones to manage her own money. Once the doctor made the diagnosis and determined my mother could not care for herself, the durable springing powers of attorney she’d signed were activated, and I was able to pay her mortgage, buy her groceries, and generally make her comfortable without much legal fuss.

In 2012, I made the hard decision to move her to an Alzheimer’s community, precisely what she did not want. Of course, we shot the moon and expected her body would go before her mind, as it had for her mother and grandmother.

We lost that bet.

My mother has been in her Alzheimer’s community for nearly 7 years now.

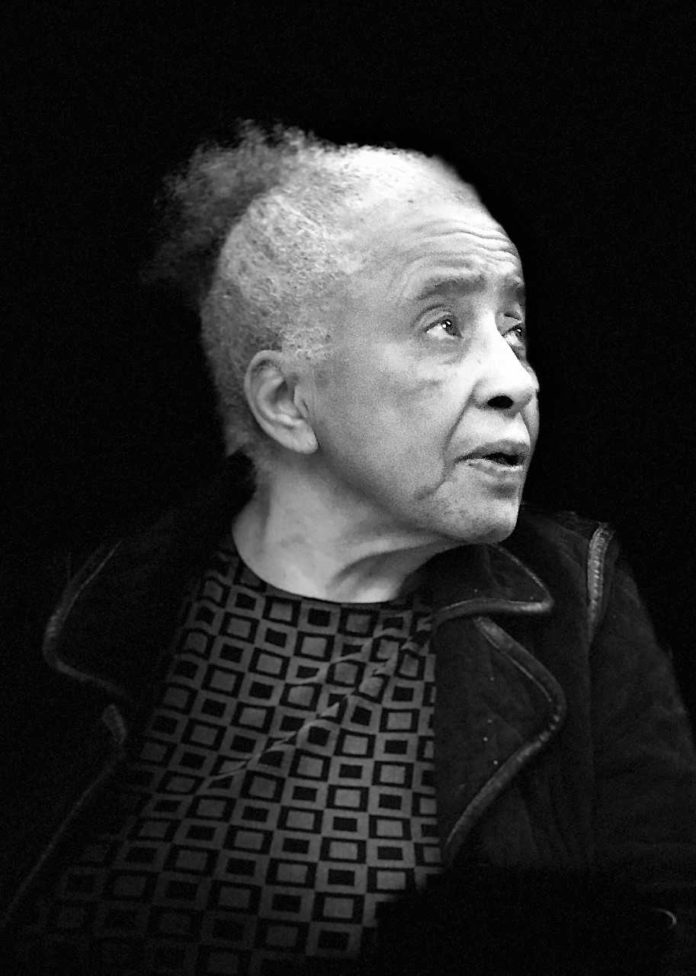

I lost and mourned whatever remnant of her was left long before about 2016. Today, she is just an old woman who vaguely resembles someone I used to know. I call her Mrs. Dillenberger when I visit. If my mother is not walking, she is eating, and she might smile at me from across the table. Usually not. There is no glimmer of recognition. My mother has only three words left, and she repeats them at random moments (“no” and “I gotta-gotta,” which are eerily accurate summations of her personality). The art books she so lovingly collected have been donated to the community library for others to enjoy; she can’t read, can’t engage. She recently fell and chipped a tooth. She would not have liked a photo showing that, so I didn’t (and won’t) take one. No one needs to remember her looking like Lucille Ball playing a hobo.

My mother is incontinent and has foot drop from botched back surgery. She refuses a cane, so she falls a lot. My mother no longer brightens when I play The Ink Spots or Dinah Washington, her favorites. Sometimes, forgetting that the food goes into her mouth, she’ll take a forkful from her plate and dump it into her water glass or soup bowl.

The residential home’s employees, mostly West Africans, call her “Mama Jean” out of respect, (at least when I’m around) and are kind when they clean and feed her. For legal reasons, they can bathe my mother but cannot cut her toenails, so I have to call a podiatrist, who sometimes doesn’t show. The workers dress her up to look nice, knowing from the clothes in her wardrobe that she would not be OK wearing the sweats or tracksuits preferred by the other residents; I appreciate this, although I don’t think she notices. They sometimes play salsa music in the kitchen, and when my mother hears it, she moves her shoulders a bit, smiles for a second, and then goes blank again. I wince seeing her fear when they undress her for bed. They are touching her without her permission, but then, she has no way of giving it.

Once in a while, my mother will let me take her hand and walk her to her room, but there is no joy in her eyes or in her grip. The next time she gets pneumonia, the doctor will call hospice instead of writing a script for antibiotics in hopes she will go naturally. We have become anti-vaxxers for everything that is not contagious (my mother would never be OK with spreading something to someone else).

That she will get sick soon is her only hope of leaving this hell. And it is hell!

I bristle when people tell me that my mother is still in there, or that I can’t be sure she has no joy. I’m sure, and no, she’s not still in there. But then, she told me that long ago. My mother’s life is like any life where you are a prisoner on a locked floor, it’s hell, and I don’t need to hear the opinions of those who fear death, or who feel compelled to provide their dime store analysis of our situation. My mother was very clear about her wishes, and I am at least grateful that when she was able, she made my job a bit easier by putting her wishes in writing.

The time is soon; now!

Get your Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) order in place today. Make sure a trusted friend knows how you feel and will carry out your wishes. File an advanced directive with your doctor and make sure it’s on file wherever it needs to be. Make clear before you are unable that your kids understand it’s your life and what you want is not negotiable based upon how they feel in the moment. If you want to pull out all the stops no matter what, that’s OK too but take the guesswork out for your family.

I could not control my mother’s illness, but my conscience is very clear.