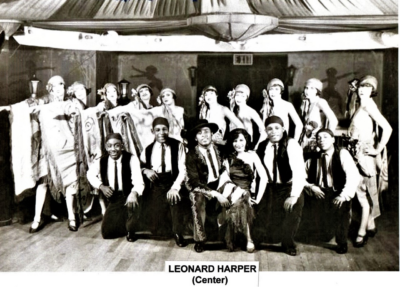

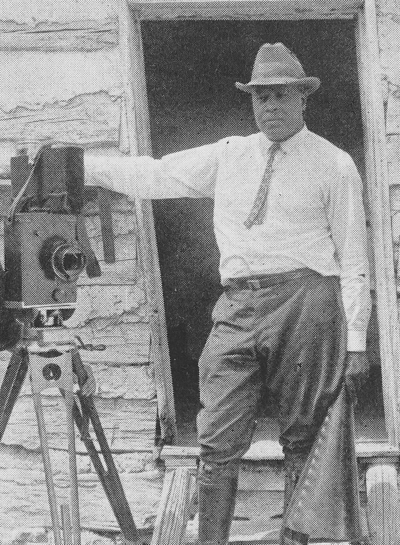

You might not know the name Leonard Harper but the unsung hero and ‘Father of Cabaret’ was one of the most influential Black producers, directors, and choreographers of the Harlem Renaissance. Throughout Harper’s short life, he pioneered the musical floor show revues of yesteryear and produced over 2,000 performances on stage and screen with some of the greatest icons in the entertainment industry. Harper’s grandson, Grant Harper Reid has spotlighted his grandfather’s extraordinary career. “My grandfather’s goal was to uplift the Black race through theater.”

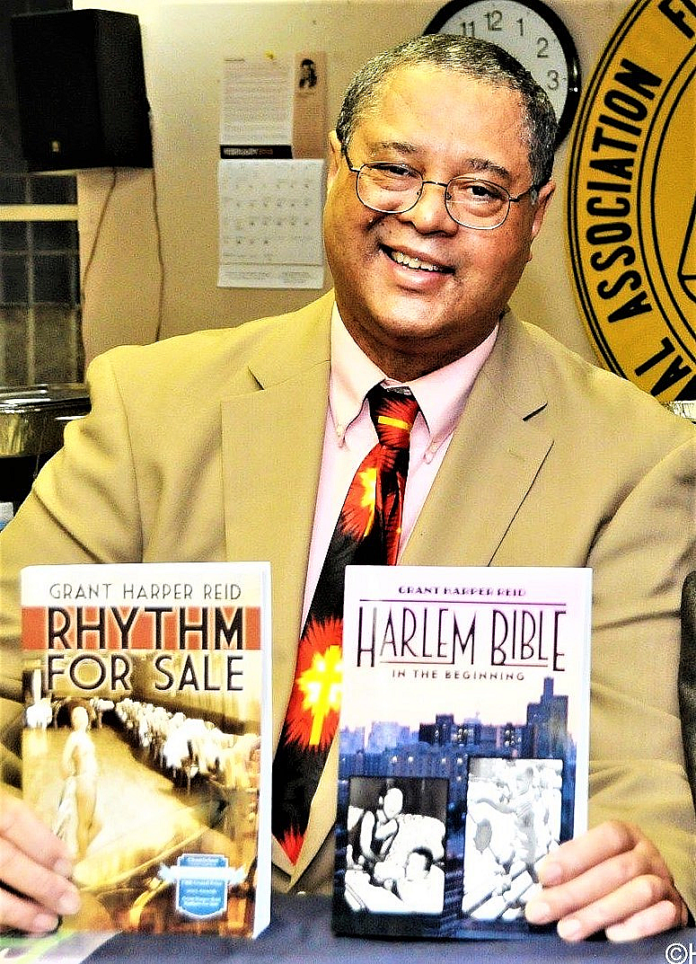

Through Grant’s tireless 20-year research and numerous interviews with folks who knew Harper, he managed to cull together fascinating information about his grandfather’s great contributions to African American culture and included them in his biographical and award-winning book, Rhythm for Sale.

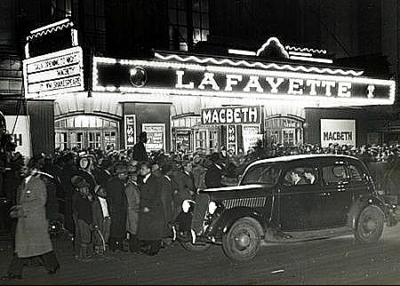

Harper held his spectacular nightclub cabaret revues during the 20s to early 40s at many of New York City’s famed entertainment venues like the Lafayette Theater, the Cotton Club, Connie’s Inn, the Apollo, and Broadway theaters. The floor shows were known for their jet-propelled theatricality that included Black awe-inspiring chorus lines and musical comedies.

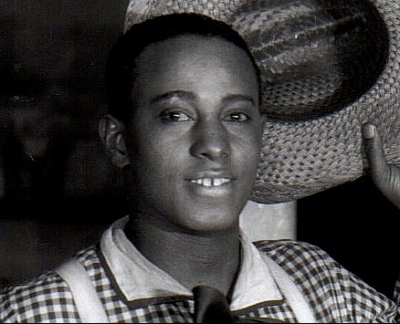

Born in 1899 in Birmingham, Alabama, Harper received his formative theatrical start as a child tap dancer. He would oftentimes tour the south in medicine shows where the talent consisted of singers, dancers, and snake charmers. As a teen, Harper worked on the T.O.B.A. (Theater Owners Booking Association) circuit and was the first colored act on the Shubert circuit of vaudeville, which was strictly staged theater, but with variety acts. He soon worked his way to New York City in 1915 but could not find employment, so he eventually left.

In the early 1920s, Harper moved to Chicago, where he met and fell in love with Osceola Blanks; the pair tied the knot in 1923. At the time, Osceola was performing as one of the Blank Sisters, a song and dance vaudeville act. After their nuptials, the duo became Harper and Blanks, the first Black act to tour on the Shubert Brothers theater circuit.

Harper’s first big revue was Plantation Days which opened at Harlem’s Lafayette Theater in 1923. The show toured in the U.S. and later, the company performed for audiences in London. In 1925, Harper opened a Times Square dance studio where patrons of all races learned dances like the Charleston, black bottom, taps, knee drops, soft shoe, buck and wing, stage dancing, and fast-stepping chorus dancing. Harper’s dance students included The Marx Brothers, Fred Astaire, and movie chorus dancers from musicals directed and choreographed by Busby Berkeley.

Up-and-coming African American entertainers who had initially worked with Harper were greatly influenced by him. He helped open doors for such luminaries as Lena Horne, Ethel Waters, Louis Armstrong, Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson, Fats Waller, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, and The Nicholas Brothers. The creative also produced many theater performances at the Apollo that showcased entertainers like Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Count Basie, The Mills Brothers, Earl “Fatha” Hines, and Jackie Moms Mabley.

Sadly, Leonard Harper died of a heart attack at the young age of 44 in 1943, while rehearsing one of his dazzling floor shows at Murrain’s Fountain Lounge and Cabaret in Harlem. The Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. officiated Harper’s funeral at Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church.

Grant has worked tirelessly to herald his grandfather’s illustrious achievements. The Bard College graduate who has also held various positions within the entertainment industry even managed to get Harlem’s Seventh Ave. between 131st and 132nd Streets to be named: Leonard Harper Way.

In addition to Rhythm for Sale, Grant also authored a second book Harlem Bible that chronicles his life growing up in Harlem and in Teaneck, New Jersey.

Get to steppin’ and learn about the fascinating journey of Grant Harper Reid’s grandfather’s amazing contributions to our culture as he discusses them with 50BOLD.

50BOLD: Your grandmother Fannie Pennington had a relationship with your then married grandfather, Leonard Harper. The couple produced a daughter, Harriet Jean Harper, who was your late mother and Harper’s only child.

Many people are only just learning about your grandfather through your book Rhythm for Sale. You tell the story of Harper’s life from his birth in 1899 to his death in 1943. He was a theatrical performer, stager, choreographer, director, and producer.

How would you describe Harper, the man?

Grant: My grandfather was a man who was at the cornerstone of the Harlem Renaissance. He was a part of the Harlem Jazz Age and the Black history experience. The reason why people don’t know about him is that a lot of his white contemporaries took credit for what he did or dismissed him entirely. There was nobody to do the research on him until I discovered his extraordinary life.

50BOLD: So, your grandfather was at the heart of the live Black entertainment shows in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance of the 20s and 30s?

Grant: Yes. Whites were coming to Harlem to see real entertainment. Although white people might have considered it slumming, they needed that infusion of soul because vaudeville was getting very stale. When Black people began fast-dancing with rhythm and jazz musicians like Duke Ellington and Count Basie, it was hot stuff.

My grandfather was a poor little pickaninny boy in Alabama and his father, William Harper, was a coon-shouter.

50BOLD: How would you describe a pickaninny?

Grant: A Black child who grew up in the south in those days had no choice but to work in the fields or clean master’s toilets. A Black child was referred to as a pickaninny if they could sing, dance, or tell jokes to entertain. White people would throw pennies at my grandfather or give him a sandwich. Whatever money or food he made would be given to his family.

50BOLD: You said Leonard’s father, William, was a coon-shouter, please explain this term.

Grant: Coon-shouters sang coon songs like I Wish My Black Color Would Fade Away.

50BOLD: Wait a minute, I have to let this sink in a minute!

Grant: Oh yes, coon-shouters sang coon songs! My grandfather moved up from being a pickaninny, to becoming a solo act. He met his wife Osceola Blanks in Chicago and they became the Harper and Blanks duo.

The Shubert brothers who were theatrical managers and producers saw my grandfather and his wife perform. They hired Harper and Blanche to be the first Blacks to travel the Shubert circuit of theaters. First, they performed in New York and then went on the road with the Shubert organization. They were on the road with entertainers like actress Lillian Gish and dancers Fred Astaire and his sister, Adele. After my grandfather’s success on the Shubert circuit, he received an offer to produce his own show, Plantation Days.

After touring the United States where Plantation Days was a big hit, in 1923, my grandfather took the show to England. It had a very short run there because of a white show called The Rainbow.

George Gershwin, who was the composer for The Rainbow went over to England at the same time. On opening night, my grandfather’s Black performers were booed because they were Black and American. The English reviews of the Black performers were brutal. The critics referred to them as animal acts. The Black entertainers were put in the basement of the theater by some water pipes. Management wanted to either pay them less or not at all. The Black performers grew so tired of the negativity they received, they couldn’t wait to get back to America.

50BOLD: What happened once Leonard and his team returned to America during the 20s?

Grant: When my grandfather returned to the U.S., the Immerman brothers–Connie, George, and Louie—immigrants from Latvia, opened up Connie’s Inn in Harlem. The club was the Cotton Club’s rival.

50BOLD: Really?

Grant: Prizefighter Jack Johnson was the first one who owned the Cotton Club, it was initially called Club Deluxe, however, he couldn’t keep it up financially. Johnson then sold the establishment to Owney “the Killer” Madden who was an Irish gangster. Owney renamed it the Cotton Club. The interior was very demeaning towards Blacks. It reproduced the racist imagery of segregation, often depicting Black people as savages in exotic jungles or as “darkies” in the plantation South picking cotton; that’s how it came to be named the Cotton Club.

50BOLD: I never knew about the origins of the Cotton Club.

Grant: When Duke Ellington and Lena Horne performed at the Cotton Club, they were not allowed to use the toilet facilities. They had to go out in the street to relieve themselves.

50BOLD: Wow, that’s a damn shame!

Grant: Meanwhile, when my grandfather returned from England, Duke Ellington and his wife, Edna Thompson moved into his apartment. My grandfather actually got Duke his earlier jobs. He got Duke work at Connie’s Inn, and the Kentucky Club previously called the Hollywood Club. Then Duke got an offer to work at the Cotton Club and this is where he really made a name for himself.

The gangster, Dutch Schultz, was Connie’s Inn silent partner. The Kentucky Club was in Times Square and run by crime boss Lucky Luciano.

50BOLD: Oh, how interesting.

Grant: Even though Lucky and Dutch were rivals, my grandfather worked for both.

50BOLD: Really! Did he work at both Connie’s Inn and the Cotton Club?

Grant: Yes, and when the Immerman brothers opened up Connie’s Inn, Dutch paid them a visit and said, “You guys know you have to pay tribute to me.” And so, they did!

50BOLD: These dealings all took place during prohibition?

Grant: Yes, and since the selling of liquor was illegal, the gangsters paid the cops to look the other way because the clubs served liquor.

When the Cotton Club first opened, my grandfather, produced the first two of three shows. My grandfather left the Cotton Club because of their outright racism. At Connie’s Inn, there was less prejudice. They gave my grandfather more freedom. The owners allowed certain Blacks into the club to see the show but would seat them by the bathrooms or kitchen.

There were mainly rich white people in attendance. At Connie’s Inn, my grandfather was told that he could only hire light-skinned Black women in his chorus line because the darker-skinned ones would scare the white patrons.

50BOLD: Oh, this is just so, so upsetting to hear!

Grant: My grandfather did not like the rules but followed them anyway. When he was working at the Kentucky Club, a lot of Broadway producers would patronize the place. One of the producers saw my grandfather’s show and decided — which was totally unprecedented at the time — that he would produce an all-Black show in one of his theaters.

50BOLD: On Broadway?

Grant: Yes, on Broadway! The white audiences marveled at the way Black people were fast-dancing. My grandfather then decided to open up a dance studio in Times Square.

50BOLD: So, would all races come to the dance studio?

Grant: Yes! The Marx Brothers would go to the studio because they wanted to learn what was called “dirty colored dancing.”

50BOLD: Why was it called “dirty colored dancing?”

Grant: Well, not only did the dance move very quickly, the movements were slightly sexual in nature. They were dance moves that whites weren’t doing. Back then, white people had to add a dirty tip to the name to make it a derogatory term.

A lot of Broadway people took lessons at my grandfather’s dance studio. Fred Astaire and his sister Adele were two of his students. Remember, Fred Astaire knew my grandfather when they were on the Shubert Theater circuit.

50BOLD: Did your grandfather teach the actual dancing?

Grant: He taught dance and hired dance instructors. The studio was fabulous with pictures on the wall of famous stars who attended.

50BOLD: Leonard Harper’s life story is one most of us never heard about. Yet, he SO influenced our culture.

Grant: It took me many years to piece together my grandfather’s journey. I had been searching for his history, but only had bits and pieces.

Here’s an interesting story I’d like to share. A friend and I visited her aunt down in The Village in New York City. We were sitting in the woman’s living room. When her elderly aunt went to get us some lemonade, I couldn’t help but notice her walk. The woman had so much rhythm in her walk. I asked her, “Were you a dancer?” She replied, “Yes!”

I mentioned to the woman how my grandfather, Leonard Harper, was a choreographer and stage director during the Harlem Renaissance. The woman replied, “I performed for your grandfather at the Apollo,” she explained. Then she gave me a big tip: “You have to go back and look at all those old Black newspapers because they wrote about your grandfather all the time.”

Well, once I was able to get hold of all those old newspapers, I began to piece my grandfather’s life together.

50BOLD: How did your grandmother Fanny meet your grandfather?

Grant: All of my grandmother’s friends were performers. They danced for my grandfather. Fanny met Leonard through her friends. They developed a relationship and fell in love even though my grandfather was married. The relationship produced my mother, Jean.

50BOLD: And your grandfather worked with Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson as well?

Grant: Yes! It was known that Bojangles always carried a gun. He scared a lot of people. He would chase folks up and down Harlem’s Seventh Avenue while threatening to shoot them. Bojangles was always accusing people of stealing his act. He even took out a full-page ad in Variety, threatening people who were stealing his dance routines.

50BOLD: Unbelievable!

Grant: My grandfather did a show with Bojangles called the Pepper Pot Revue. My grandfather had Bojangles dancing up and down the stairs with his female chorus line called The Harperettes. When Bojangles performed his tap dance, The Harperettes would follow his routines. It was a sold-out show at the Lafayette Theater.

50BOLD: Circling back, you mentioned that at Connie’s Inn, your grandfather had to get rid of the dark-skinned performers?

Grant: Yes, my grandfather had to get rid of his dark-skinned chorus line because the white audiences would complain. When he eventually went to the Apollo he was able to integrate his chorus lines with different hues.

50BOLD: And Leonard also directed an all-Black musical revue in 1929 called Hot Chocolates that was quite a hit.

Grant: The music for Hot Chocolates was by Fats Waller, lyrics by Andy Razaf, and directed by my grandfather, Leonard Harper. There were 219 performances in 1929 from June to December. Three creative Black men were the talents behind the show; it was a huge hit.

50BOLD: Tell me about Leonard Harper and his interaction with the actress Mae West?

Grant: Mae West was cool with Black people. She did a show for my grandfather in Brooklyn with Black talent. She performed on Broadway with a lot of Black people. Many white Broadway people were so mad at her for working with Black folks that they made up a rumor that she was a man.

50BOLD: So Mae was Black-friendly.

Grant: Mae had a Black boyfriend, Johnny Carey, who was one of the two Black guys who owned the after-hours spot, the Nest Club in Harlem. It was around the corner from the Lafayette Theater. A lot of gangsters hung around the Nest Club. My grandfather dressed the chorus line like birds because they were performing at the Nest. Mae would hang out at the club.

Yes, Mae West hung around a lot of Black people and was very Black-friendly. In 1934, she made a movie re-enacted from her Broadway show Constant Sinner called Belle of the Nineties. She had Duke Ellington in the movie as an actor and music composer. It’s wonderful!

50BOLD: So, Mae West was influenced by Black people.

Grant: Yes, when Mae walked she would shake her hips and all that. Mae even spoke slang, trying to sound like a Black woman.

50BOLD: How fascinating! And Mae West worked with your grandfather in Brooklyn. Grant, you are really dropping a lot of history that most of us are so very unaware of.

You mentioned how Busby Berkeley, who was considered to be one of the greatest white choreographers of American movie musicals, wasn’t as talented as he was perceived to be. He just stole other people’s work, in particular from Black folks like your grandfather.

Grant: There wasn’t any rhythm with Busby’s dancers in his movies. He sent his chorus line over to my grandfather’s Time Square studio to get some soul. My grandfather’s Black dancers would go see a Busby Berkeley movie and would snicker. Why? Because they knew Busby got the dance steps from my grandfather.

The famed TV variety show host, Ed Sullivan, also got a lot of his ideas from my grandfather. Sullivan used to be a syndicated columnist for New York’s Daily News. He used to attend my grandfather’s variety revues and learned everything he could from him. When Sullivan produced his first Broadway musical Harlem Cavalcade in 1942, he hired my grandfather as the choreographer.

50BOLD: Really! What about the connection to Malcolm X and your grandfather?

Grant: It’s in his book, The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Malcolm speaks about how the old-timers reminisced about the good ole days seeing spectacular live Black showcases at Connie Inn, the Cotton Club, and The Lafayette Theater.

When my grandfather’s career started to wane, he was reduced to performing in Harlem nightclubs like Small’s Paradise where Malcolm X worked as a waiter.

50BOLD: How did your grandfather die?

Grant: He died of a heart attack while rehearsing his chorus line at Murrain’s, a club in Harlem. He just fell out. They took him to Harlem Hospital where he was pronounced dead.

50BOLD: Regarding the Harlem street, Leonard Harper Way, named in 2015 on the southwest corner of 132nd St. and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Boulevard (also known as Seventh Ave), how did the sign come about?

Grant: I managed to get the street sign up because a few people felt they could take advantage of me. People were trying to take my research, produce plays and use my work without my permission. I just said, ‘Wait a minute. Let me claim this.’ That’s when I decided to not only write the book, but to further claim it, I decided to get a street named after Leonard Harper where he conducted most of his work.

The street is called Leonard Harper Way and it’s where Connie’s Inn, The Lafayette Theater, and my grandfather’s office were located when he and Oscar Micheaux directed the first all-Black talkie.

50BOLD: Wait a minute, Leonard worked with the great, Black, pioneer filmmaker Oscar Micheaux? What did they work on?

Grant: The movie is called The Exile. It was the first all-Black talkie movie (1931). It was produced by my grandfather’s boss Frank Schiffman who owned the Lafayette Theater and who also co-owned the Apollo at one point. Oscar Micheaux was trying to work with my grandfather for a long time because he wanted to utilize his talent. Oscar knew my grandfather could help him depict nightclub scenes in his movies.

Leonard teamed up with Frank to make The Exile. It was filmed in Fort Lee, New Jersey at the Metropolitan Studios, but the production office was between 131st and 132nd Streets on Seventh Avenue. On the same block as the office was the famous “The Tree of Hope,” where Black people used to rub an elm tree for good luck. The stump of “The Tree of Hope” is now located on the Apollo stage. Since so much of my grandfather’s work was accomplished at the production office’s location, I strived to get 132nd Street and Seventh Avenue named “Leonard Harper Way“ and thankfully, I obtained enough signatures and support to get the job done.

50BOLD: Besides the book and street sign, do you have any other plans to keep your grandfather’s legacy alive?

Grant: People have approached me with ideas, but I have turned them down. If the right project comes along, I’m open to it. I’ve spent so much time doing research on my grandfather’s life.

50BOLD: Do you see a movie or a documentary about Leonard Harper in the future?

Grant: Yes, if it’s done with the right people.

50BOLD: What final words do you have for our 50BOLD audience who will be reading and learning about this phenomenal unsung pioneer in the Black live entertainment arena?

Grant: I urge your readers to get a copy of Rhythm for Sale (available at Amazon.com). What you will get from the book is an authentic representation of my grandfather’s life, straight, no chaser from a Black perspective. The book also discusses his friends and colleagues in the business.

We need to record and define our own history. If we don’t, other people will. They’ve been doing it. It’s time for us to take hold of our own narratives and truly define them with no sugar-coating.