If I could steal one final glance

One final step

One final dance with him

I’d play a song that would never ever end

How I’d love, love, love

To dance with my father again

Speak to me Luther!

Wonder why Luther Vandross’s Grammy Award-winning song floated through my head last Sunday, a week before Father’s Day? I had been struggling with the right way to approach the Father’s Day article that the 50BOLD.com managing editor asked me to write. I hadn’t gotten anywhere until I heard Luther.

Suddenly, I wanted to “dance with my father again,” the way I did at my wedding reception 14 summers prior. In the nine years since Daddy left the planet, I’ve been processing my complicated feelings about him, both in therapy and in my mind. I’ve hated him for about two years now, mad at all the mean things he said to and about me while he dwelled on earth. Why did I suddenly miss and want to be with my father?

While he was alive, I worshipped the ground on which Arthur Burit Hill, Sr., walked. Daddy was my first love, my Electra complex. I know most of you ladies can relate. Daddy was my Higher Power. I idealized this devoted but sometimes brutal man and looked up to him for advice and comfort. As you can probably guess, that need for approval from this giant, and my solicitation of it would often boomerang, as I would frequently receive hurtful responses. Like a mid-80s baseball throw by New York Mets star pitcher Doc Gooden, Daddy’s responses were unpredictable. He would often hurl one-liners barbed with insult and pain to the outfielder; I caught the ball every time.

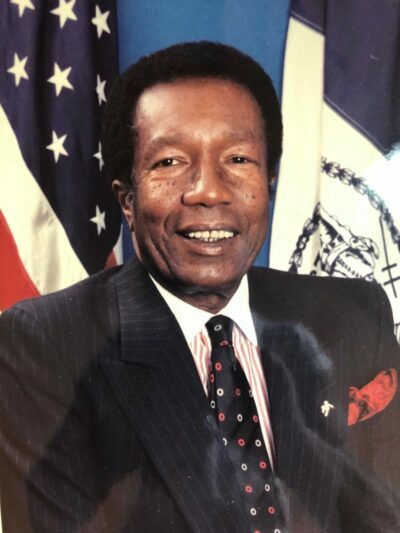

In his prime, Daddy was a good-looking, dark-skinned, tall, strapping man of 6 feet, complete with what in 2019 might be termed “classic sub-Saharan African features.” At some point, Daddy suffered an illness that left him with one shoulder higher than the other. In the 60s and early 70s, I sometimes visited Dad at his police precinct in Harlem. Once outside, Daddy would wave, and flash his signature face-wide, toothy grin at admiring passersby, who greeted him with, “Evening, Inspector Hill.” He knew everyone on those inner-city streets! For Daddy was both a World War II veteran and a 26-year New York Police Department member. He retired from the NYPD as an Assistant Chief.

My father’s next career move was private industry. He had a 17-year stellar career at United Parcel Service. When he retired from UPS, he was a well-respected lobbyist and a vice president. One former lobbyist said Dad was considered “the Dean of the Black lobbyists on Capitol Hill.”

I both idealized my father, and was afraid of him, for reasons I shall later reveal.

So here I am. How can I articulate with pen my evolving and revolving thoughts about this larger-than-life man who reached up to Heaven and chose me? Or did I select him and this family, as some spiritual teachings suggest?

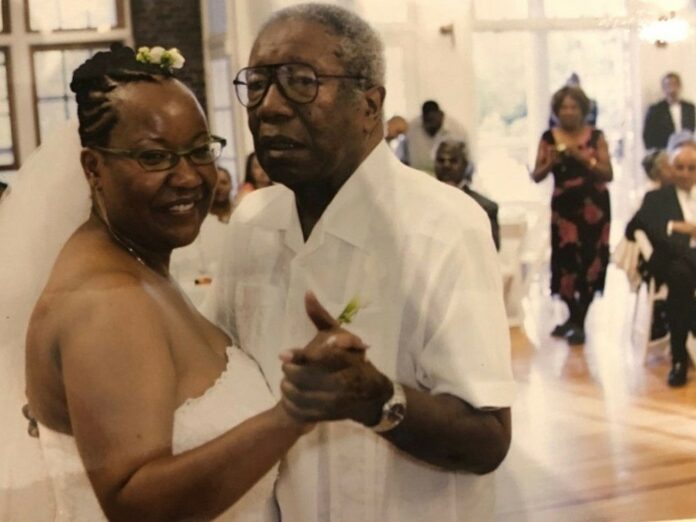

To help me connect, I located my long-banished 2005 wedding pictures. Shots spurned for years because that marriage ended when it began. I knew I’d find a picture of the traditional father/daughter dance. What was apparent in these photos was how frail Daddy looked, five years before he would commune with God. I always saw my father as strong and fierce, up to the day of his unexpected and quick departure. I never thought he would leave. Daddy was so strong; and he would last forever on earth, taking care of me and the rest of his brood.

Daddy’s arthritic knees became so painful that for several years prior to my wedding, he refused to dance with Mommy or me at the Comus Social Club New Year’s festivities held at the event venue Terrace on the Park in Queens. Instead, Daddy would hold court, as was his custom, talking up a storm. He’d occasionally glance at the sashaying dancers on the congested dance floor.

Having such mobility problems must’ve been hard on Daddy’s pride. For at past parties, I had danced enough West Indian calypso and soca with him to know the truth. My mother would reminisce that during their year-long mid-50’s courtship, “Your father and I loved to go dancing. At the dance hall, we were the first couple to arrive, and the last one to leave.”

But when his eldest daughter got married, Daddy stood up and danced with her.

That’s how much he loved me. In later life, Daddy would frequently exclaim, “Vicky, you know you’re my favorite.” I would respond, “Don’t say that in front of the others!” I felt guilty that he was singling me out.

“Finally got a girl,” my father remarked lovingly to his bride of four years after I plopped out on a cold December evening back in 1960. Mommy had already produced two handsome and healthy sons, back-to-back. I became a definite Daddy’s girl, much like the sister who would arrive six years later. And I look just like my father–same broad forehead, same eyes, same big lips—wonderful, Nigerian style. My friend Judyth Watson-Remy of 50BOLD.com bellowed, after viewing those wedding photos of us dancing, “You and your Dad look like twins!”

So it is so hard to believe that when I was in 11th grade, Daddy joined the other haters – my brothers, neighbors, schoolmates, and disclosed, “You will never be beautiful!”

Nowadays, I wonder if Daddy thought I was ugly because he hated how he looked? Shameful to say that in 2019, we still have to deal with almost daily discrimination and racism. Watching TV news, you receive the subtle message that most young Black men are criminals. And those of us blessed with dark skin and Negroid features hardly see ourselves on television, magazines and the arts, with the exception of the occasional Viola Davis. I think, and I’m not alone, that despite the “Black is Beautiful” movement of the 70s, Black people who look like me, 180 degrees from Beyoncé and Rihanna, are generally not considered attractive. If you don’t think I’m telling the truth, ask any Black man if they believe songstress Nina Simone was beautiful.

Need I say more?

In addition to all this negativity that is the birthright of every Black person in the U.S., my Dad lamented that when he was in public school, “they called us ‘god-damned monkey-chasers!’” The phrase was a derogatory label for a West Indian immigrant or descendant. Being Black and from the Caribbean was a double-negative in Harlem during the 1920s. To add insult to Dad’s emotional injury, in terms of looks, Dad’s younger brother was considered “the handsome one,” of the family, as God outfitted my uncle with a Roman nose, thin lips, and wavy hair. Mommy and I did find Daddy attractive but in his developing years, that might not have been the general consensus. Daddy said relatives would grab his broad forehead and say, “This is where the brains are.” Daddy was called “the smart one.”

Well, wherever the hell my father’s feelings originated, about his or my looks, I heard his pronouncement and internalized it, along with everyone else’s cruel comments. Only now am I starting to unpack that negative baggage. Though to be truthful, when growing up, I never considered my father handsome. I never even thought about it. He was just my big, strong Daddy, of whom, for reasons that will become obvious, I was afraid.

Daddy soon had to take special care of his third child. I suffer from schizoaffective disorder, a chronic mental illness that appeared at age 16 and still lingers. At 19, I had to leave undergraduate studies at the University of Pennsylvania, and my psychiatrist prescribed medicine to treat my symptoms. I soon discovered that consuming tasty West Indian comfort starchy delights like boiled flour dumplings, peas and rice and plantain, gave temporary relief from my emotional pain by producing a little “high.” And for some unknown reason, I was always hungry. Soon I was cramming an extra meal into my day. I, who never before had a weight issue, quickly shot up 11 pounds. “Watch it; you’re gaining weight!” My Jamaican boyfriend’s sister scolded.

This upward movement that was registering on my scale, my father just couldn’t stomach. He kept telling me to diet which I would, for a time. After my second suicide attempt, which landed me in the local hospital Emergency Room, I was sent upstate for what became a 2-month stay at a renowned mental hospital. When discharged, I was virtually depression-free. I was also sporting an extra 25 pounds.

Dad used the drive back home to vehemently blast and belittle his 21-year-old and newly well adult daughter. “Just look at you, Vicky. You’ve gained so much weight. You look terrible. Now you look just like your grandmother (his mother). You’re going on a diet, now!” I felt ashamed and sad. My own father was rejecting me, yet again. I also felt not good enough, a core negative belief that was planted in childhood. I would suffer a 37-year ride on the weight gain rollercoaster. I was obsessed with food. My self-esteem disappeared when I was heavy. If Daddy had done his research, he’d know that my illness, and the medicine regimen combatting it, caused most of the weight gain.

“Lose 10 pounds before you can go to the Sundowners picnic,” Daddy sarcastically asserted.

Daddy was a member of a lot of bourgeois African American social clubs, which were chock-full of what he termed “the beautiful people.” They were slender, well-coiffed, and well-heeled. As you can probably guess, my weight stayed the same, and yours truly was not invited to attend the Sundowner’s picnic. This man who “loved” me would routinely exclude me from social events if I was too heavy for his liking. I felt neglected, rejected, and left out. I also felt powerless over the desire to overindulge in nourishment.

When the first two depressions came at age 16 and 19, I was frequently sad and tearful. My father would make fun of me. “You sound just like a baby,” was his refrain. In my childhood, I would definitely cry upon receipt of one of my Dad’s World War II military, policeman-style spankings. He then barked, “Want me to give you something to cry for?” Meaning another hit. Daddy’s threat would immediately shut me down. And you know what? Till the present time, I have difficulty releasing my emotions through tears. I just can’t cry.

Daddy didn’t understand my mental illness. I suspect he blamed its manifestation on me, as did our Episcopal family priest. At age 19, amid that second major depression and with no recovery in sight, my father took me to see Father E. for counseling. I smelled a rat immediately upon entering Father E’s office. I took note of the gruesome depictions of late-term abortions, complete with doctors pulling out almost fully developed babies that adorned his walls. Father E. certainly let his politics be known.

This gaunt, white man of the cloth closely resembled the traditional Caucasian version of Jesus Christ, with his straight black hair and pointed beard. A most somber priest, Father E. never smiled, but he was a caring man, and his large, South Bronx church was always packed. I had known Father E. all my life and felt both love and respect for him. That evening, Father informed me, “Your illness is retaliation from God for something bad you did earlier in your life.” I wondered what that could have been. I hadn’t been an earthling that long. Why would God turn on me so viciously at my tender age? Didn’t the old Negro spiritual proclaim, “Suffer the little children to come unto me?”

I must say that after our chat, I never felt the same about Father E. Enough about his “religious” diagnosis which by the way, I also shoved inside.

At age 16, amid the first depressive episode, I tried to cut my wrists with a razor blade. Couldn’t finish the job. It was too painful. I went to my parent’s bedroom and showed them the red-stained markings. My father took one look at me, then threw a punch that knocked me to the floor. Next morning, Mommy and I boarded a train for a week’s sojourn at an upstate YMCA hotel, but it was really to get me out of sight.

With all my father’s damaging conduct, you must be wondering, “Why in the world would Vicky WANT to dance with her father, let alone see him again?”

Well, as therapists have told me, hurt people hurt people. After my father’s alcoholic and abusive father deserted the family, Daddy’s mom, who was morbidly obese and cleaned houses for meager pay, had to support and raise her three young children. Mama struggled with this Herculean task amid the Great Depression. My father knew how it felt to want what his mother couldn’t afford, like toys. Daddy fought to rise from poverty and made a great life for his wife and family.

But Daddy never forgot his humble beginnings. As a retiree, he always flew Economy, when he could easily afford first class seating and amenities. He actually traveled business class the years he crisscrossed our country lobbying for UPS. On someone else’s dime, Daddy had gotten quite used to good treatment. But when HE was doing the spending, especially on himself, Daddy was frugal to no end.

Daddy’s father physically abused him. He never forgot the time in Staten Island when his father, “broke a broomstick over my head.” Daddy’s sister told me that once Papa went to hit Mama and when Daddy intervened, he received the force of his drunken father’s rage.

Daddy then verbally and physically abused me and my siblings, unfortunately, this is a natural, though negative, generational behavior flow.

Although his words could inflict pain, my Daddy was always there for me. During my junior year at Penn, my parents visited me because I was so sick. We attended Sunday worship at my church. During the after-mass coffee hour, Daddy retreated to a window. I strolled over to him and saw that he was quietly but hysterically crying. I had never witnessed that!

“I’m scared for you. I don’t want to leave you here. I just want you to feel better,” Daddy mumbled into his hands between tears. He was bent over and in apparent grief. He had spent the previous semester commuting to Philly for weekly family therapy with him, Mommy and me. The psychiatric social worker often admonished, “You’re too close to your father, and you have no relationship with your mother!”

“I will get better, Daddy!” I promised,” not anticipating that getting well would require two years at home and twin hospitalizations. Daddy admitted to me years later that going through that traumatic experience with me was when I became his favorite child.

Seeing how his chasing a solid education aided him in his careers, Daddy saw to it that his children received good schooling. We were the first Black family to integrate an elementary school in Flushing, Queens. Daddy paid most of my undergraduate and graduate expenses. He gave us a Black cultural heritage. Every Friday after school, Daddy would take us to see a show at Harlem’s famed Apollo Theater. Countless times, I viewed James Brown don his special cape and croon, “Please, please.” We would participate in Harlem Week activities in the summer. We explored Harlem that Black Mecca, years before white people began to try and take it back. I also remember viewing 8-hour operas in European languages at Lincoln Center.

Although Daddy once declared he would “never set foot” on his mother’s birthplace of St. Maarten, he did so in 1973 to join me. We both fell in love with the lush, scenic, quaint island home of our ancestors. Thirty-five years ago, Daddy bought a timeshare at a sprawling Dutch-side resort. Some of my happiest memories are from when I was there with my parents during their two-week December stay. Daddy and I would lounge most days on the apartment veranda, debating any subject that arose.

While a police administrator, Daddy had gone to night school and earned a Master’s degree. He had a sharp intellect and devoured the New York Times. The man could converse about most topics. One issue I learned to avoid was police brutality cases. While being a Black American, Daddy was also a former cop. He would analyze the facts and generally side with the police.

Then there was the love that Daddy did manage to smother me with. Remember his declaration that I was his favorite? Daddy offered sound business advice that aided me in my role as manager of a midsized library branch. Daddy was a better father to us as adults. And he taught by example those themes he considered important for life, like developing a good work ethic, voting in every election, attending church regularly, and loving Black culture. He and my mother taught us to “shop Black” or patronize Black stores and professionals. In his later years, Daddy was a comforting presence in our family. He became that good father I so desired, though still spouting the occasional mean retort.

Last but not least, Daddy’s hard work and frugal lifestyle left us a tidy financial inheritance. With the monies, I was able to wave goodbye to Brooklyn renting and purchase a cozy condo in a nearby lovely new building complete with elevators. I also travel, and as a retiree in my mid-50’s, I am young and healthy enough to actually still enjoy life.

Thank you, Dad, you’re taking care of your family from beyond the grave!

And thank you, Luther Vandross, your heavenly work on me is done. Planting the song “Dance with My Father” in my brain helped me realize and value my blessings enough to create an ode to my Daddy, just in time for Father’s Day.

Daddy, may I have the next dance?