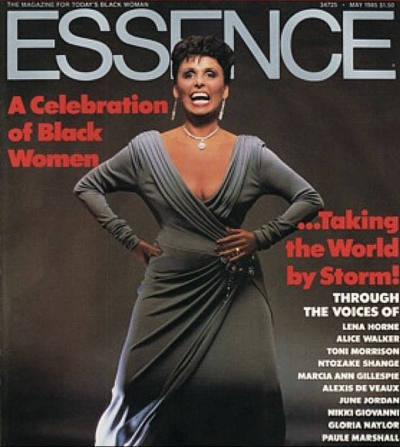

I moved to NYC in 1985 after securing a job at Essence magazine. I first worked in the art department as an art coordinator. One of my duties at the magazine was to return unused film to the photographer who shot it, then archive what had been used. I had worked on the Essence May 1985 silver anniversary issue where the beautiful actress and songstress Lena Horne was featured.

I remember viewing the raw, unretouched images of the stunning Lena Horne who at the time was 68-years-young. She wore a gorgeous full-length silver gown that added to her already very present regalness. Lena was a true legend, an entertainer who my mother and grandmother admired greatly; she was indeed our queen.

Lena Mary Calhoun Horne was born on June 30, 1917, in Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn to Edna Scottron, an actress, and Edwin Horne, Jr., a civil servant with a sideline in illegal gambling. Edwin always lived high on the hog and never went to jail. He later owned a hotel and a restaurant. Lena’s family were reportedly descendants of John C. Calhoun, Vice President of the U.S. from 1825 until 1832. They were also descendants of favored slaves privileged Blacks who, by virtue of their brains had worked in the house, not in the field. The Hornes were a bourgeoisie middle class with family members who had graduated college and held distinguished positions in organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League. Even though Lena’s father left the home when she was three, he remained an integral part of her life.

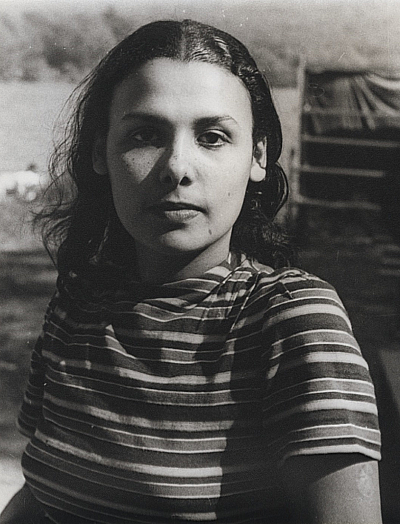

Since Edna was part of a Black theater group that traveled frequently around the country, Lena was mostly raised by her grandparents Cora Calhoun and Edwin Horne. Cora’s militancy involved deep prejudice. Lena would later say that she’d ‘been raised to dislike white people intensely.’ Cora forbade her to play with white children but wouldn’t explain why. By the age of five, Lena was sent to live in Georgia and eventually traveled the road with her mother; she often missed school. At age of 12, Lena returned to N.Y.C. where she briefly attended Girl’s High School in Brooklyn (now Boy’s and Girl’s High School), then wound up dropping out at age 16.

The era in which Lena grew up was a difficult one for many light-skinned Blacks, who were both welcomed and discriminated against by their own and by whites alike. Lena was teased as a youngster for being light-skinned, but in fact it was her complexion that actually launched her career. Lena was hired to dance in the chorus line of Harlem’s famed Cotton Club after dropping out of high school and also began taking voice lessons. The beauty also managed to land a small role in an all-Black Broadway show, Dance with Your God.

In 1935, Lena became a featured singer with the Nobel Sissle Society Orchestra. Two years later, she met and married one of her father’s friends, Louis Jones, the son of a Pittsburgh preacher and brother of the city’s first Black councilman. The couple lived in the Hill District, and Horne sometimes provided entertainment at events hosted by rich families. “I sang around at parties in Pittsburgh, for money,” Horne said in a 1963 interview with Ebony magazine. The marriage produced two children, Gail and Edwin; the couple divorced in 1944 over issues with finances. Sadly, son Edwin passed away in 1971 from kidney failure.

Lena’s next stage experience was with the Lew Leslie review Blackbirds of 1939 and Blackbirds of 1940. During the same year, Lena joined a popular white swing band called the “Charlie Barnet Orchestra.” While traveling with the band, the young performer experienced racial prejudice; she was often ostracized and denied entry into hotels and restaurants.

The blatant racism Lena seemed to face everywhere while on the road quickly became too much for her to deal with so she left the orchestra gig. She was able to secure a long-term engagement at the popular club Cafe Society Downtown in N.Y.C. Lena decided to immerse herself in learning as much as possible about her Black culture. Lena also reunited with childhood friend, singer, and political activist Paul Robeson, who would later be the cause of her being blacklisted during the McCarthy era. The relationship the two shared would completely change her life’s path politically, as she would later become a mouthpiece for the Black community.

In 1943, Lena began a booking at the Savoy Plaza Hotel. She also landed a small number of film appearances and a feature in Life Magazine. Lena signed a seven-year contract with Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM) and she became the first highest paid African American entertainer in the U.S. She was also the first long-term contract ever given a Black player in Hollywood. The studio bosses positioned her as the “acceptable” face of modern African American beauty. In 2010, after Lena’s death, daughter, Gail Lumet Buckley discussed in an interview with NPR, the issues her mother had with the film company as the first glamorous Black actress in Hollywood. Black actors typically played stereotypical roles in Hollywood, toms, coons, bucks, mulattoes, and mammies but Lena helped change the game:

“She was Walter White and Paul Robeson’s test case. She was the test case of the NAACP, which had decided they were going to change the image of Hollywood. She was the test case. And that made her the enemy of a lot of Black actors in Hollywood who were very upset. And they said you’re trying to take work away from us. There’ll be no more jungle movies. There’ll be no more old plantation movies. What are you trying to do? And Paul Robeson said to her: These people aren’t important. The people who matter are out there, the Pullman Porters, those people, and they want to see a new image, and you’ve got to do it. And she said okay. Robeson wanted her to refuse to play a domestic, to refuse to play any role that was demeaning to Blacks and to stick by that and not be swayed from it.”

The light-skinned actress who was too light for the other Black actors, yet too Black for white films in highly segregated America appeared in I Dood It (1943), Swing Fever (1943), and As Thousands Cheer (1943). She was also the lead in the all-Black cast of Cabin in the Sky (1943) a film that is regarded as her finest performance. In the movie, Stormy Weather (1943) co-starring Ethel Waters, Lena sang the title song which became her signature tune in later years. Unfortunately, Lena’s scenes were often filmed separately so they could be cut when screened for southern audiences.

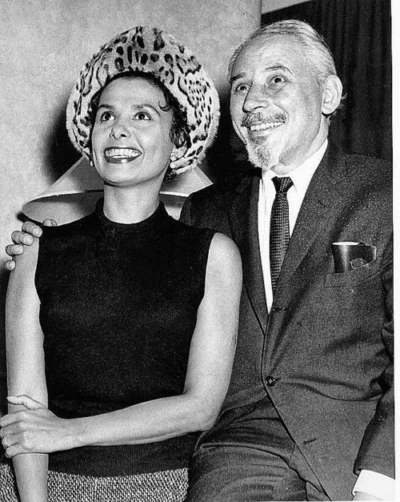

In 1947, Lena secretly married white Jewish composer Lennie Hayton whom she met while under contract with MGM. He became her musical director, pianist, conductor and manager. The marriage was strained from the start because it was an interracial one which was taboo in the 40s and 50s. Lennie was also reportedly a heavy drinker and smoker, but the couple remained married until his death in 1971. Lena admitted that she had married the Oscar-winning musical director to advance her career and cross the color line in show business but later learned to love him.

After her contract ended with MGM Lena found herself blacklisted from Hollywood because of her associations with pro-Black activists Robeson and W.E.B Du Bois. Even though Lena was absent from the screen, she found incredible success performing in nightclubs and recording. As a matter of fact, Lena’s live recording, Lena Horne at the Waldorf Astoria, would be the biggest-selling album in the history of the RCA Victor label.

On the civil rights front, Lena worked with Eleanor Roosevelt to pass anti-lynching laws and spoke out against the treatment of African American soldiers during the war. In the 60s, Lena was avery present in the civil rights movement across America. She performed at rallies in the south on behalf of the NAACP, and the National Council of Negro Women. She attended the March on Washington, and met John F. Kennedy as well as Medgar Evers. She worked tirelessly to further the rights of her people and in 1999 was awarded the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Jazz Artist.

Lena also appeared on numerous popular television variety and comedy shows at the time and was given her own network special in 1970. Surely, we all remember Lena’s 1973 appearance on the hit TV comedy, Sanford and Son, where she played herself!

In 1971, Lena suffered a succession of personal blows. She lost her husband Lennie, followed by the deaths of both her father and son. Lena’s last on-screen acting gig was in the 1978 film, The Wiz, where she played Glinda the Good Witch.

In 1980, Lena announced her retirement which was short-lived when she was booked for a four-week performance at Broadway’s Nederlander Theater. The show was entitled, Lena Horne: The Lady and her Music which was a huge box-office success. Lena was honored with a special Tony Award, and two Grammy Awards for the cast recording of her show.

On May 9, 2010, the great Ms. Lena Horne died of congestive heart failure at the age of 92. Thousands gathered at St. Ignatius Loyola Church in Manhattan to mourn the world-class performer who dazzled the globe with her beauty and talents.

You are never forgotten Ms. Horne!