We are all surrounded by change; some of us are touched by dramatic and life-altering situations that may force us to reconsider how we live our lives. We cannot avoid the unexpected events in our lives. What we can control is how we choose to respond to them. Verda Byrd was 70-years-old when she stumbled upon a secret that was incomprehensible; she was not born African American, and her birth parents were Caucasian.

The impact of learning as an adult that you are not the person you believed you were for your entire life (at your core) can be devastating. After Verda’s adoptive parents had passed away, she accidentally came across her birth certificate and discovered that her birth name had been Jeanette Beagle. She was taken aback. After delving further into her background, Verda unearthed some shocking news that her biological parents were Daisy and Earl Beagle, a poor white couple with four other children at the time of her birth.

Earl Beagle wound up abandoning his family in 1943, and Daisy sustained a traumatic injury after falling from a trolley. The unfortunate events lead to the Beagle children becoming wards of the state. Daisy later regained custody of all of her children except for Verda, who was given up for adoption as a young child.

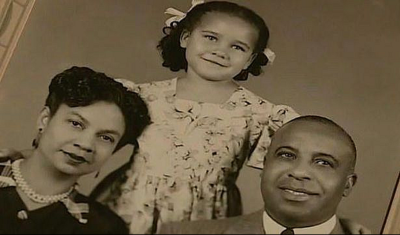

Adoptive parents Ray and Edwinna Wagner, who were well-to-do, changed Jeanette’s name to Verda Ann. Since Edwinna was light-skinned, there were no raised brows or whispers about Verda’s fairer complexion. Verda grew up in Newton, Kansas as an only child and claims she never experienced racism or bullying in her small community even though she was light complected and raised during segregation. At age 12, Edwinna decided to inform Verda about the adoption but neglected to mention that the child was Caucasian; it was a secret she took to her grave.

Verda, who had never met her birth parents, eventually, visited her biological mother’s grave. In 2014, she also managed to track down three of her biological sisters. Verda reunited with her siblings, Sybil Panko, Debbie Romero, and Kathyrn Gutierrez, but the much-anticipated gathering was short-lived when Panko dropped the n-word. Panko died in 2016, and Verda was reportedly barred from the funeral; Panko had allegedly made the request in writing. Byrd’s relationship with her remaining siblings is estranged.

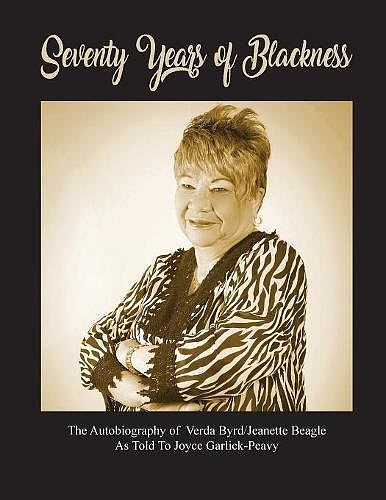

The twice-married mom of one has written about her experience in an autobiography titled Seventy Years of Blackness which details her search for her biological parents and what she learned along the way. Verda who has stated how she has no regrets or ill feelings towards anyone is content with the life she has carved out for herself. “Mother took me to a Black hairdresser, and I grew up participating in Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. marches and eating soul food. My life was completely immersed in Black culture, and why wouldn’t it be? For all intents and purposes, I was Black,” Verda has stated about the life she’s lead over these past decades.

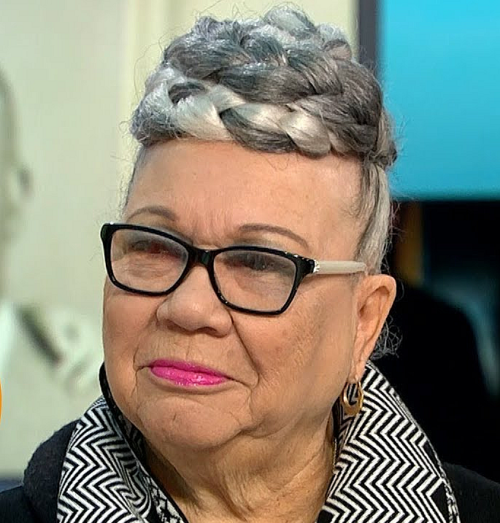

Now, at age 78, when Verda shares her story, curious minds always want to know if she considers herself to be Black or white. Read on and find out….

50BOLD: How and when did you find out you had been adopted?

Verda: At the age of 12, yes, my mom told me I was adopted but my mind could not comprehend what the word ‘adoption’ meant. My adopted mom also never told me I was white; she never shared this with me.

50BOLD: Do you know why you were put up for adoption? How old were you when the adoption took place? Do you know why you were given up?

Verda: I don’t know my biological parent’s reason for giving me up for adoption because I never knew them. I was only about four years of age or maybe even younger when I was placed in a children’s home. I can only assume that my biological parents were financially unable to raise their children at the time and I was number five. I think finances were the biggest reason for giving me up.

50BOLD: Did you ever feel a connection to the white race in any kind of way? Growing up, did you ever question your ethnicity, anything ever happen to give you pause, any red flags?

Verda: Growing up there were no red flags to make me question my ethnicity. At the time, there was only one high school in my mostly white town. So, everyone knew each other; I never felt anything that made me wonder about myself.

50BOLD: Interesting how you felt no connection to white people at all! Most of us have experienced some form of racism, especially in high school. I went to an all-white high school and a few of the kids there would throw things at us Black kids. Did you ever deal with racism from whites? What about from our folks, do you remember being made to feel uncomfortable because we were critical of your light complexion and straight hair?

Verda: I grew up in the 40s and 50s in Newton, Kansas. In grade school, high school, or in the town itself, I never experienced any form of racism; I was very fortunate.

50BOLD: Well, racism is definitely something I know about. When you discovered you were actually Caucasian, how did you deal with the news?

Verda: After I found my birth certificate, the adoption papers came to me later in the mail. When I opened the envelope and began reading the documents page-by-page, I thought that maybe they had been sent to the wrong person. Maybe the mailman meant to deliver the package to someone else. So, I kept reading and re-reading the documents and the words never changed. I think I even threw the papers on the floor at one point. I thought the documents were a bunch of crap.

50BOLD: Did you request the adoption papers?

Verda: Oh yes, I requested the adoption papers because I needed answers.

50BOLD: Did you cry when you found out about your biological parents or were you angry at your adoptive parents for keeping the secret?

Verda: I didn’t cry when I found out I was white because I was in shock. You think you’re a particular race for 70 years and then a document enters your life that changes it all.

50BOLD: Did your husband or children change towards you at all? Were they dumbfounded? Supportive? What was their reaction to it all?

Verda: I have one child, a daughter who is in her 50’s. She doesn’t live where I currently reside which is Texas. I went over the adoption documents with my husband of 42 years who said, “Verda, what are you talking about? Oh, let me see those papers!” Here’s the thing; my husband accepted the situation. There were no issues as far as my husband was concerned. He still loved me and my race did not matter to him at all.

50BOLD: Okay, what about your husband’s extended Black family, how did they react? Did any of them change towards you; were they standoffish?

Verda: No one changed towards me because in my husband’s family there are biracial people—grandkids, nieces, and nephews. So, my race was not an issue for them.

50BOLD: When you are asked about your ethnicity now, how do you respond?

Verda: I actually write down ‘H’ for human and ‘O’ for other. I take ‘other’ to mean ask me if you really want to know!

50BOLD: When Verda Byrd looks in a mirror who does she see, a Black woman or a white woman?

Verda: When I look in a mirror, I see a Black woman. I’ve gotten older and my skin tone has gotten darker, but that’s natural. So, I look in the mirror to make sure I’m still just Verda Byrd.

50BOLD: Do you feel comfortable in either world, Black and white? Do you feel different moving in any one particular world?

Verda: I don’t feel any different moving in either world because as I’ve stated, I’m still Verda. I’ve also been a military wife and have lived overseas. I experienced no racial issues. People would just ask me what country I came from. My race didn’t seem to matter. On my passport, I don’t even know if my race is mentioned on there. So, when you are overseas and go to Paris for example, they’re not asking you what race you are to get on a bus. They just want to know where you are going and that’s it!

50BOLD: Have you met your white family members? Were they welcoming? Have you remained in contact with them?

Verda: I did find my white relatives. Yes, we did reunite; I met my sisters, nephews, and other family members. I basically know all of them and they know me. But there are family issues, whether I like it or don’t like it. Every family has issues. One of the family members lives three hours from me, and my birth mother is buried 3 hours from me, in Dallas.

50BOLD: Have you visited your biological mother’s gravesite?

Verda: Yes, in 2014, I traveled to Dallas because I found out where my biological mother was buried. I received the information from some documentation. I visited the gravesite and wished her a Merry Christmas.

50BOLD: Are your biological parents buried next to each other?

50BOLD: Are your biological parents buried next to each other?

Verda: No, no! My birth mother Daisy is buried in Dallas. My birth father was cremated and is in Omaha, Nebraska.

50BOLD: Why share your story? What made you decide to let go of your privacy?

Verda: Adoption is an ongoing forever story. My birth mother and father gave me up for adoption because they loved me enough to do so. I hold no hard feelings towards them. They did what they thought was best for me. People will often ask, if whether I think my life would have been better had I stayed with my birth parents. I don’t know and I don’t really care! I have to thank the Lord for the good life that he did provide for me.

50BOLD: When your mom told you, did she want you to look for your birth mom?

Verda: No, my adopted mom told me about the adoption when I was 12 years of age. Well, in my 12-year-old mind, it didn’t mean a thing. And so that was all she ever, ever said about it. She didn’t want anybody to know her business. She was very private. When she passed, I had to break open her desk to find documents like insurance papers because I wasn’t given a key.

50BOLD: Do you think your adoptive mom would be happy to know that you found out about your birth mom?

Verda: No. I don’t think my adoptive mom would have been happy that I found anyone in my family because evidently, she didn’t want me to know in the first place. We never discussed my adoption during my adult years; she never mentioned it.

50BOLD: I can’t believe no one in your adoptive family said a word to you about your adoption. They held on to the secret pretty well!

Verda: My dad’s sister, who lived in Kansas City where my parents adopted me, she knew. When my mom and dad adopted me from the children’s agency and took me to their home, there were others who knew, but then, they all passed away. So, when I became an adult, there was nobody living who could provide me with information about my birth parents.

50BOLD: When did your adoptive parents pass away?

Verda: My adoptive mom and dad died 35 years ago.

50BOLD: And how long did it take you to get the information about your birth parents?

Verda: About three months.

50BOLD: Did you have to go to court to request the documents from your birth?

Verda: Well, I wrote to the juvenile court system in Kansas City where I was born to request my adoption documents. The courts, in turn, had to request permission from a judge to release information to me.

50BOLD: Did your siblings know you had been adopted?

Verda: No, they didn’t know.

50BOLD: I wonder, did your parents ever meet your birth mom?

Verda: Back then, adoptive parents and birth parents were not allowed to meet.

50BOLD: You’ve written a fascinating book about your life entitled Seventy Years of Blackness. There is also a documentary, Seventy Years of Blackness: The Untangling of Race & Adoption by Christopher Windfield that peers into not only your life but examines the effects race played within the adoption industry. The documentary won a Magnolia Independent Film Festival Award this year for Best Short. How can our readers purchase your book and get more information about the film?

Verda: My book can be purchased on Amazon. For more information about my documentary, contact Dr. Keandra Tatum at verdabyrdbooking@gmail.com. I also founded the Seventy Years of Blackness Scholarship Project and we are trying to raise funds to support the educational needs of young adults between the ages of 18-25. Our committee would like to give at least eight educational scholarships per year to deserving students who are seeking to attend trade schools in fields such as barbering, cosmetology, or culinary. For more information about the scholarship fund, visit our GoFundMe page.