Black is beautiful, Black is excellent.

Black is pain, Black is joy, Black is evident.

Black is so much deeper than just African-American.Black is growing up around the barbershop.

Black is stepping in for your mother because your father’s gone.

Black is being forced to leave the place you love because there’s hate in it.Black is struggling to find your history or trace your roots.

Black is being strong inside while facing defeat.

Black is being guilty until proven innocent.But Black is all I know, there ain’t a thing that I would change in it.

Culled from Santan Dave’s “Black”

We have contributed in so many ways to this society and are often not given the credit we deserve. Black History is a reminder to reflect on the sacrifices, hard work, and creativity of Black leaders and innovators of this country.

There are so many unsung Black history-making heroes who do not occupy much space, if at all, in our history books, and here, we pay tribute to seven of them…

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler (1831-1895)–After working as a nurse for eight years, Rebecca Lee Crumpler longed to be a doctor, but there were no Black female physicians in the U.S. at the time. Rebecca’s nursing skills were so highly recognized by the doctors she worked for in Charleston, Massachusetts, that they actually sent letters of recommendation to the New England Female Medical College so that she could be admitted there. In 1860, Rebecca was accepted to the college, which was created to educate women on female health concerns. At the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, Rebecca was forced to relocate to Richmond. When she returned, the school’s administrators had canceled her scholarship. Rebecca didn’t succumb to institutional racism and won tuition from the Wade Scholarship Fund established by the abolitionist Benjamin Wade. In 1863, during her medical studies, Rebecca’s husband died of tuberculosis, but she forged on. At her final examination with two white women, she was accused of “slow progress” that led the practitioners to “hesitate very seriously on recommending her.” Because the examining practitioners didn’t give evidence to substantiate their claims, she received her medical degree in 1864, becoming the first Black female doctor in the U.S. Upon graduating, Rebecca moved to Richmond, Virginia, where she cared for freed slaves without access to medical care. She was the author of the 1883 Book of Medical Discourses in Two-Parts, which was the first African American academic textbook. The book guided women on how to care for themselves and their children.

Claudette Colvin (1939 – )–On March 2, 1955, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin was on a Montgomery, Alabama city bus on her way home from school when the driver demanded she give up her seat to a white passenger. Claudette said she would have gladly given up her seat to an elderly white person, but the passenger was not a senior. The teen’s defiance resulted in police being called to the scene. Claudette was dragged off the bus and manhandled by two officers as she kept reminding them of her constitutional rights. The child was handcuffed, placed in an adult jail, and charged with violating segregation laws, disturbing the peace, and assaulting a police officer. She pleaded not guilty but was convicted. (Two of the charges were dropped on appeal.) After Claudette was released from prison, there were fears that her home would be attacked. Members of the community acted as lookouts, while Claudette’s father sat up all night with a shotgun in case the Ku Klux Klan turned up. Claudette was the first person to be arrested for challenging Montgomery’s bus segregation policies, so her story made a few local papers – but nine months later, the same act of defiance by Rosa Parks was etched in stone.

Maria P. Williams (1866–1932)–Before Oscar Micheaux, there was Black filmmaking pioneer Maria P. Williams who is credited as being the first Black woman film producer for the silent crime drama, The Flames of Wrath in 1923. The former school teacher had a history of activism, independence, and interest in the liberal arts, which led her first to newspapers, then to film production, script-writing, acting, and finally, a memoir in 1916 entitled, My Work and Public Sentiment. In the book, Maria identified herself as a national organizer and speaker with the Good Citizen’s League and stated that ten percent of the proceeds would go to suppressing crime among African Americans.

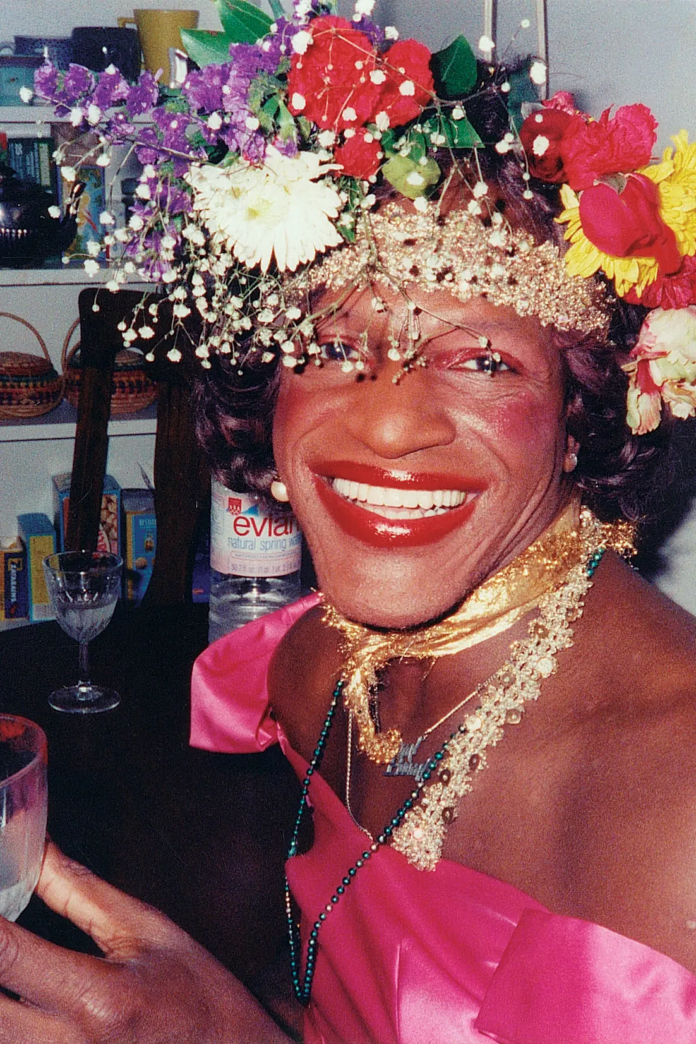

Marsha P. Johnson (1945 – 1992)–Many folks are unfamiliar with the influential role Marsha P. Johnson had on the drag and queer culture. Johnson, a Black transwoman and activist, stood at the forefront advocating for homeless LGBTQ+ youth, those affected by H.I.V. and AIDS, and gay and transgender rights. Assigned male at birth, Marsha grew up in an African American, working-class family in Elizabeth, New Jersey. She enjoyed wearing dresses starting at age five. After graduating high school, Marsha moved to New York City, where she returned to dressing in women’s clothing and adopted the full name Marsha P. Johnson; the “P” stood for “Pay It No Mind,” a phrase that became her motto. She described herself as a gay person, a transvestite, and a drag queen and used she/her pronouns; the term “transgender” only became commonly used after her death. In addition to being the co-founder of STAR, an organization that housed homeless queer youth, Marsha also fought for equality through the Gay Liberation Front. In 2020, New York State named a waterfront park in Brooklyn for Marsha. She is also now the subject of many documentaries.

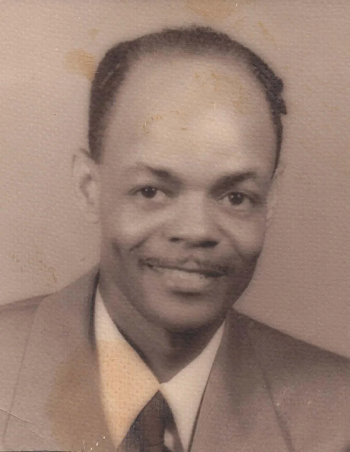

Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. (1880-1970)–The first Black general to serve in the U.S. Army was Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. He rose to sergeant major within two years and earned a commission as a second lieutenant in 1901. In the next four decades, he served in Liberia and the Philippines and taught military science at the Tuskegee Institute and at Wilberforce University. All of Benjamin’s duty assignments were designed to avoid a situation where he might be put in command of white troops or officers.

Benjamin became the first Black colonel in the U.S. Army in 1930, and ten years later, he was promoted to brigadier general. During World War II, he was in charge of a special unit charged with safeguarding the status and morale of Black soldiers in the army and served in the European theatre as a special adviser on race relations. After serving 50 years in the military, Benjamin retired in 1948.

Robert Sengstacke Abbott (1870 – 1940)–As the child of former slaves, Robert Sengstacke Abbott studied the printing trade at Hampton Institute from 1892 to 1896. He received a law degree from Kent College of Law, Chicago, in 1898, but because of racial prejudice in the United States was unable to practice. In 1905, Robert founded The Chicago Defender newspaper with an initial investment of 25 cents. The Chicago Defender, which was once heralded as “The World’s Greatest Weekly,” soon became the most widely circulated Black newspaper in the country, making Robert one of the first self-made African American millionaires. Surging on the tide of Black migration north and west, the paper’s circulation reached 50,000 by 1916, 125,000 by 1918, and more than 200,000 by the early 1920s—overall readership tripled those figures. Abbott urged Blacks to fight for equality, once promoting the anti-lynching slogan, “If you must die, take at least one with you.” He banned the terms Negro and Colored as undignified; instead, The Chicago Defender consistently used the phrase the Race. White efforts to keep The Chicago Defender out of the South only raised its standing among Black readers. The Chicago Defender also contributed broadly to the development of a national African American culture. One of the paper’s longtime contributors, Langston Hughes, who developed the beloved character Simple in his columns, characterized the newspaper as “the journalistic voice of a largely voiceless people.” The Chicago Defender still exists today but as a digital.

Otis Boykin (1920 – 1982)–Talk about someone who loved tinkering! Otis Boykin was truly a creative extraordinaire. He invented more than 25 electronic devices, including chemical air filters, burglar-proof cash registers, and electronic resistors that control missiles. One of Otis’ most important contributions to science was that his work enabled control functions for the first successful, implantable heart pacemaker. Upon graduating from Fisk University in 1941,Otis went to work as a laboratory assistant, testing automatic aircraft controls. In 1944, the young inventor decided to work for himself, devoting most of his brain power to the emerging field of electronics. Otis’ achievements led him to work as a consultant in the United States and in Paris from 1964 to 1982. Over the course of his life, he earned over 25 patents.