My earliest memories of Kwame Nkrumah were shortly after the coup de tat in Ghana on February 24, 1966. I was 7 years old then. I recall a sense of jubilation and at the same time a dark, foreboding cloud that hung over the nation at his overthrow. I was born in Ashanti, the heartland of the National Liberation Movement (NLM)- which was the major opposition to Kwame Nkrumah and his Convention People’s Party (CPP) government. My grandfather was a CPP supporter. He recounted violent clashes between the CPP and NLM in Ashanti in those days. Like many of my generation, it was much later in life that I got to know the man and what he stood for.

Born on September 18, 1909, in Nkroful, Ghana, Francis Nwia-Kofi Nkrumah was born in a polygamous family setting where his father, Kofi Ngonloma, from the Akan tribe and a goldsmith by profession, had many wives and children. His mother, Elizabeth Nyaniba, was a retail trader, and Nkrumah was her only child. Nkrumah’s mother strongly insisted that he start his formal education at an early age. His father supported the idea and Nkrumah was sent to a local elementary school operated by a Roman Catholic mission. He disliked going to school at first but eventually looked forward to attending every day. Nkrumah was such an exemplary student that he became a pupil-teacher in middle school.

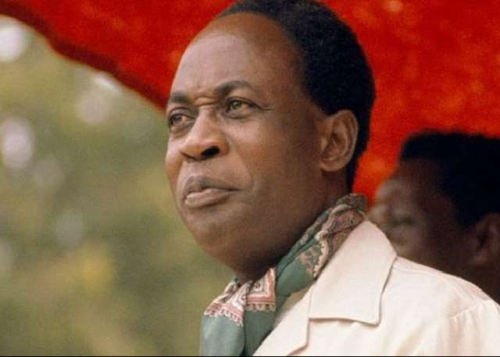

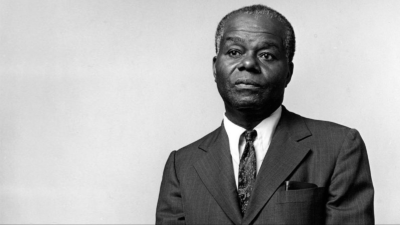

Nkrumah stands as a towering figure, a beacon of liberation, and a champion of African unity. As the first Prime Minister of the Gold Coast and President of Ghana, Nkrumah’s impact reached far beyond the borders of his nation, shaping the course of the African continent’s struggle against colonialism. Yet, to understand the man behind the myth, one must delve into the influence that Black America exerted on his character, politics, and vision for Africa’s future.

At the heart of Nkrumah’s connection to Black America was in fact, his education. Unlike many of his peers on the Gold Coast who had their higher education in Britain, the colonial mother country, Nkrumah chose the United States instead. This choice was inspired by Dr. J. E. Kwegyir Aggrey. Dr. Aggrey was popularly known as “Aggrey of Africa” because of his scholarship and intellectual achievements. He attended Livingstone College in 1898 in Salisbury, North Carolina, and continued at Columbia University. As the first African Vice Principal, he taught Nkrumah at Achimota College in Accra which inspired him greatly.

Nkrumah received both his Bachelor of Arts (1939) and Bachelor of Theology (1942) from Lincoln University and continued his education at the University of Pennsylvania, where he received a Masters of Philosophy and a Masters of Education (1942, 1943). While in college, Nkrumah became increasingly active in the Pan-African movement, the African Students Association of America, and the West African Students’ Union.

In order to take care of himself and fund his education, Nkrumah worked many odd jobs. He was a fish and poultry seller on street corners in Harlem, a counter at a shipyard, and a seafarer during the summer months. He also spent much of his free time preaching at Black Presbyterian churches on Sundays.

Nkrumah made connections with organizations like the Republican and Democratic parties, Council on African Affairs, the Committee on Africa, the Committee on War and Peace Aims, and several others. His idea was to learn the art of effective organization, as he recognized that this would be crucial in addressing the colonial question upon his return to the Gold Coast.

An important aspect of Nkrumah’s time in the United States was his encounter with Pan-Africanism. From the writings of W.E.B. Du Bois and others, Nkrumah absorbed the principles of unity, self-determination, and liberation that underpinned the Pan-African movement. He recognized in the struggles of African Americans a mirror of the African experience—a shared quest for dignity, equality, and sovereignty.

Nkrumah also formed friendships with several African American leaders. He met Dr. W.E.B. Dubois in the 40s. At the improbable age of 93, Dr. Dubois landed in Ghana in 1961, officially to take up the editorship of the “Encyclopedia Africana” at the invitation of now President Kwame Nkrumah. Dr. Dubois would die and be interred in Ghana as a Ghanaian citizen on August 27, 1963. His former residence in Accra, now the W.E.B. Dubois Center, is a Pan-African Cultural Centre. Dr. Dubois even dedicated his poem, Ghana Calls to Kwame Nkrumah.

Prominent Afrocentrist and historian, Dr. John Henrik Clarke and Nkrumah, knew each other during the Harlem History Club days which was a study circle founded by Harlemites in the heart of Harlem in the 30s, and based at a YMCA. Clarke said this of Nkrumah, “My impression of him was not as a future head of state but an African who would go back and make a major contribution to his nation. He was a committed African.” Years later, in the 60s, Dr. Clarke found himself stranded in Accra when he visited Ghana. Nkrumah, then President, spotted Dr. Clarke among the throngs who had lined up to watch his motorcade. This highlights an Akan proverb that says, “One does not light a lamp to recognize in the dark someone they know.” President Nkrumah stopped his motorcade to go chat with Dr. Clarke. He wound up offering Dr. Clarke a job as a journalist on his newspaper, the Accra Evening News.

Nkrumah visited the U.S. in July 1958, and a major rally was organized in Harlem to receive him. It was during this event that he was introduced to Malcolm X. They developed a relationship that lasted until Malcolm’s assassination in 1965. Nkrumah and Malcolm X met again in 1964 when Malcolm X visited Ghana.

In 1945, Nkrumah left the United States for London, England, at the end of his 10-year educational odyssey. A befitting last hurrah for him in his adventures in living, learning, and teaching in the United States was his being voted in the Lincolnian Magazine of Lincoln University in 1945 as “the Most Outstanding Professor of the Year.” This was a testament to his remarkable impact on the academic community, and the indelible mark he left on the hearts, and minds of his students.

Nkrumah spent two years in England from 1945 to 1947. Initially, he enrolled to complete his Ph.D. at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). But he soon abandoned this for his political activities. In May 1945, Nkrumah helped organize the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester, England. This congress brought together African and diaspora leaders to discuss colonialism, independence, and unity. He also established the West African National Secretariat.

In December of 1947, Nkrumah arrived back on the Gold Coast after being away for 12 years. He returned at the invitation of J.B. Danquah and the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) to take up the position of general secretary. The UGCC was the leading political movement that was working for the independence of the Gold Coast. It was made up of elite business people and educated professionals. From the onset, this arrangement of Nkrumah and the UGCC was not a match made in heaven. The pace at which the UGCC wanted to prosecute the independence agenda, “independence in the shortest possible time” was at odds with the fire branding urgency with which Nkrumah, radicalized by his Pan-Africanist experiences abroad, approached the matter, “independence now!”

Nkrumah broke away from the UGCC to form his mass party, The Convention People’s Party, in 1949. Through struggle, imprisonment, and internal opposition and sabotage, Nkrumah won independence for the Gold Coast, which became Ghana on March 6, 1957. This is what Dr. Clarke said about the independence of the Gold Coast concerning the African American civil rights struggle, “It was a major impact on Black America because it came at a time when the civil rights movement was reaching a crescendo, a great height.” At independence, Nkrumah declared, “The independence of the Gold Coast is meaningless unless it is linked with the total liberation of the African Continent.”

Martin and Coretta King attended Ghana’s independence ceremony at the invitation of Nkrumah. Dr. King was impressed by Nkrumah’s leadership and keenly aware of the parallels between Ghanaian independence and the American civil rights movement. While in Ghana, the Kings shared a private meal with Nkrumah, discussing nonviolence and Nkrumah’s impressions of the United States. In response to King’s assassination in 1968, Nkrumah wrote: “Even though I don’t agree with [King] on some of his non-violence views, I mourn for him. The final solution of all this will come when Africa is politically united. Yesterday it was Malcolm X. Today, Luther King. Tomorrow, fire all over the United States.”

As President, Nkrumah proceeded to build his new nation along socialist lines, while at the same time spearheading the Pan-African agenda and the movement for the liberation and ultimate unification of Africa. But the forces against him were formidable. At home from some of the African leaders and from the West who, caught in the throes of the Cold War with Russia, were wary of Nkrumah creating a socialist United States of Africa.

Many believed Nkrumah was assassinated, there were six attempts on his life that were spread over the period of his presidency. Nkrumah was ousted in a coup d’état on February 24, 1966. In August of 1971, he traveled to Romania for prostate cancer treatment and passed away on April 27, 1972.

Ghana pioneered the road to independence for much of Africa. Nkrumah left a stamp on Ghanaian history that continues, long after his death, to fascinate and inspire many of his countrymen as well as people all over the world of African descent.

Edward Kusi, who stands for the betterment of humanity is a lifelong student/teacher in this adventure called Life. Edward lives in Accra, Ghana and loves reading, writing, and researching. He is currently working on a biographical novel about the life of the great Kwame Nkrumah.