We are spotlighting this month among our pages, former publisher extraordinaire Ed Lewis, a co-founder of the magazine that forever changed my life, Essence.

When I moved to New York City from Detroit in the 80s, I was hired to work at Essence which was a dream come true. I lived for every issue of the magazine because it truly was a kind of Black woman’s Bible. Essence magazine was my guiding light, it contained features with advice that was as inspiring as some biblical passages. Working at Essence magazine really changed the trajectory of my life and I will forever be thankful to Mr. Ed Lewis.

In our feature on Mr. Lewis, he proudly discussed his cousin Barbara Rose Johns, whom he greatly admired. She was a civil rights leader and sadly, one whose name was unfamiliar to me. I had not come across this fearless activist’s name in any of my studies. Barbara was an unsung shero who at age 16, led a Prince Edward County Virginia 400-plus student body in protest against inequality and all during the Jim Crow era.

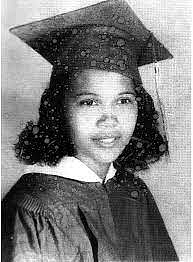

Barbara Rose Johns was born on March 6, 1935 in New York City to Robert and Adele Violet Johns; she was the eldest of five children. The family, who was originally from Prince Edward County Virginia, moved back home after Robert joined the army during World War II. Adele and her children stayed with her grandmother.

Johns’ uncle, Reverend Vernon Johns, a known a civil rights activist, would often visit the family. He would oftentimes preach to the family the importance of Black history. Johns was an avid listener, so her uncle’s important teachings did not fall on deaf ears.

Johns was educated at a segregated public school, and could never get used to their separate and unequal system. She eventually attended the all-Black Robert Russa Moton High School which was built in 1939 to house 180 students but was busting at the seams with a 400-plus student body. Johns was on the school’s debate team and when she traveled to other schools, she got to witness firsthand, how the white learning institutions were well-equipped, and rich in resources compared to Moton.

During the winter months, it was so cold inside Moton that students wore coats to stay warm. Whenever it rained, buckets were strategically placed inside the school to catch water leaks. Moton had no science lab, gymnasium, and even lacked adequate restroom facilities. Since the school was overcrowded, educators often found themselves teaching outdoors, in the auditorium, and even on school buses. Students had to share secondhand desks, books, and equipment. Parent’s complaints to the school board were just an exercise in futility, nothing got done to improve the poor conditions at the school.

The school buses used by Moton were secondhand, in constant disrepair, and broke down frequently. On March 19, 1951, a tragedy occurred that spurred Johns to organize the strike. A Moton school bus broke down on some train tracks and was hit by a train. Sadly, five students lost their lives. One of the victims, Hettie Dungee, was Johns’ best friend.

On April 23, 1951, 16-year-old Johns organized her fellow students and teachers to strike after a meeting in the school auditorium. The young activist encouraged the protestors to march out of the building and to not return, until county officials agreed to desegregate a white high school, or build a new one.

The students remained on strike for two weeks, eventually arranging a meeting with the school superintendent who only wanted them to resume classes. The students then decided it was time to sue the county. They met with Rev. L. Francis Griffin, pastor of the local First Baptist Church, and a very active participant with the state chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Rev. Griffin encouraged Johns to contact NAACP attorneys Oliver W. Hill and Spottswood W. Robinson III. Initially Hill and Robinson did not want to take on the case but changed their minds after meeting with protestors. On May 23, 1951, they filed Davis v. County Board of Prince Edward County.

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County was one of the five cases combined into Brown v. Board of Education, the famous case in which the U.S. Supreme Court, in 1954, officially overturned racial segregation in U.S. public schools.

Not long after the strike, Johns received numerous death threats, and there was a cross burning on the Moton High School grounds. Johns’ parents feared for their daughter’s safety and sent her away to live with her uncle in Montgomery, Alabama for her senior year of high school.

On May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme Court would rule that “in the field of education the doctrine of separate but equal had no place.” The Prince Edward students had won a major victory, but the fight wasn’t over yet. Many state leaders in the South collectively refused to budge with regards to desegregation, a movement that became known as “massive resistance.” In 1959, Prince Edward County was finally forced to comply with the decision but instead opted to close all public schools to avoid desegregation. Schools remained closed from 1959 to 1964. Only through years of demonstrations, a visit from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and another U.S. Supreme Court case, did the schools reopen in Prince Edward County.

Robert Russa Moton High School would become Mary E. Branch #2 and operated in some capacity until 1991. A few citizens approached the county and raised over $300,000 to purchase the original Moton High School. The building became a National Historic Landmark in 1998 and the Moton Museum opened in 2001 on the 50th anniversary of the historic 1951 student walkout.

Johns went on to attend Spelman College in Atlanta. However, she interrupted her studies when at 19-years-old, she married William Holland Rowland Powell, despite a 13-year age difference. The couple moved to Philadelphia. Johns worked as a school librarian for two decades and William became a Baptist minister. The couple raised five children and lived a quiet life. She also went on to earn a college degree in 1979 from Drexel University.

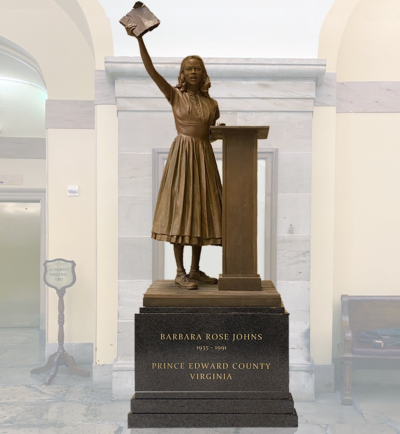

In 2008, a civil rights memorial was erected in Richmond behind the governor’s mansion. The monument features Barbara Johns and other prominent Virginia civil rights activists. In 2018, April 23 was declared Barbara Johns Day in the Commonwealth of Virginia. In 2022, a statue of Barbara Johns was selected to replace the statue of Robert E. Lee in the Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C. which will be erected later this year.

Barbara Rose Johns died in Philadelphia on September 25, 1991 from bone cancer at age of 56 years old.