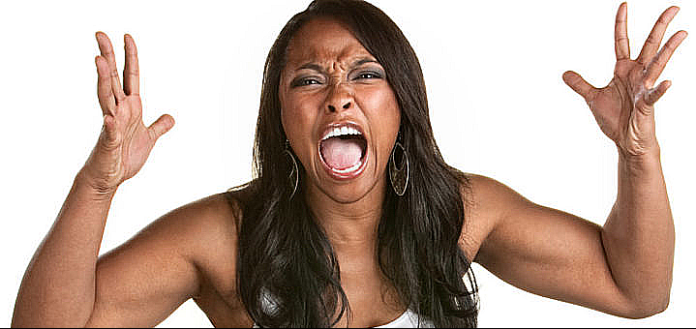

Many people think that anger is caused by hormonal changes or brain activity. This is only partly true. Researchers have found that while hormones play a role in an angry response, there is always a cognitive (thinking) component. Some people think that humans are innately aggressive or warlike. While our behavior is sometimes hostile toward others, anger is not part of our basic nature.

Frustration may lead to aggression, but it is not inevitable. Some people respond to frustrating events with anger, while others don’t. Anger is only one response to frustration. In many cultures, people are taught to respond to frustration in other ways.

Since Freud’s day, mental health professionals have disagreed about the value of venting feelings. It may surprise you to know that today’s research shows that expressing anger often results in more irritation and tension rather than feeling calmer.

Why Expressing Anger Can Be Bad for You

Giving vent to anger can produce the following kinds of harmful effects:

- Your blood pressure increases

- The original problem is worse rather than better

- You come across as unfriendly and intimidating

- The other person becomes angry with you as a result of your behavior

Physical Effects of Anger

Heart – Researchers at Stanford University have found that of all the personality traits found in Type A patients, the potential for hostility is the key predictor for coronary disease. The combination of anger and hostility is the most deadly.

Stomach and intestines – Anger has a very negative effect on the stomach and has even been associated with the development of ulcerative colitis.

Nervous system – Anger is bad for you because it exaggerates the associated hormonal changes. Chronic suppressed anger is damaging because it activates the sympathetic nervous system responses without providing any release of the tension. It is a bit like stepping down on a car’s accelerator while slamming on the brakes.

Why We Get into the Anger Habit

Anger is our response to stress. Many times we feel anger to avoid feeling some other emotion, such as anxiety or hurt. Or we may feel angry when we are frustrated because we want something and can’t have it. Sometimes, feeling angry is a way of mobilizing ourselves in the face of a threat.

Anger may be useful because it stops (blocks) stress. Here are two examples:

You are rushing all day in your home office to meet an impossible deadline. Your daughter bounces in after school and gives you a big hug as you furiously type on your computer. You snap, “Not now! Can’t you see I’m busy?”

You have just finished taking an important exam. You have studied for weeks and the result is very important to your career. You fantasize all the way home about dinner at your favorite Italian restaurant. When you get home, your husband has prepared a steak dinner for you. You yell, “Why don’t you ask me before you just assume you know what I want?”

This explains why people often respond with anger when they experience the following kinds of stress:

- Anxiety

- Being in a hurry

- Being over stimulated

- Being overworked

- Depression

- Fatigue

- Fear

- Feeling abandoned or attacked

- Feeling forced to do something you don’t want to do

- Feeling out of control

- Guilt, shame, or hurt

- Loss

- Physical pain

What to Do Instead of Getting Angry

Here are some constructive things can you do to reduce stress—instead of becoming angry:

- Do relaxation exercises

- Get physical exercise

- Listen to your favorite music

- Make a joke

- Play games

- Say it out loud

- State your needs assertively

- Take a nap

- Tell a friend about it

- Work

- Write about it

New Responses to Stress

An angry response often results when we are unhappy with someone else’s behavior. Here are some other responses you can choose instead of flying off the handle:

Set limits – Let’s say a friend hasn’t returned a book you loaned to her. Now she wants to borrow another one. You could say, “I’m not going to be able to lend you this book until you return the first one.”

Don’t wait – When you realize that you’re feeling annoyed by a situation, speak up. Don’t wait until your annoyance escalates to anger.

Be assertive – Say in a positive way what you want from the other person. For example, say, “Please call me when you get home,” rather than, “Would you mind giving me a call when you get there?”

4 Ways to Stop the Spiral of Anger

Call a time-out – This is a very effective technique for breaking the sequence of behavior that leads to a blowup. It works best if it is discussed ahead of time and both people agree to use it. Here’s how it works: Either person in an interaction can initiate time-out. One person makes the time-out gesture like a referee in a football game. The other person is obligated to return the gesture and stop talking.

Check it out – If anger is a response to personal pain, it makes sense to ask the other person, “What’s hurting?”

Make positive statements – It may be helpful to memorize a few positive statements to say to yourself when your anger is being triggered. These statements can remind you that you can choose your behavior instead of reacting in a knee-jerk manner—for example, “I can take care of my own needs,” “His needs are just as important as mine,” “I am able to make good choices.”

Be prepared with a memorized response – Here are a few statements and questions which will help deescalate anger:

- What’s bothering me is…

- If it continues like this, I’ll have to take care of myself

- What do you need now?

- So what you want is…

Richard B. Joelson, DSW, is a clinical social work psychotherapist, educator. Dr. Joelson’s private practice in New York City provides counseling and psychotherapy services to individuals and couples. He is the founder of richardbjoelsondsw.com and author of the book Help Me!: A Psychotherapists’s Tried-and-True Techniques for a Happier Relationship with Yourself and the People You Love