People have long pointed to worldwide racism–especially in France—as some sort of rationalization for American racism. A recent Black American expat argues that such comparisons don’t really add up when it comes to the French.

Any country that honors the one Black man who kicked its ass in a war—a war over slavery, no less—is fine with me. That country is France, the place I fled to following the election of Donald Trump. “But the French are racist too!” people would invariably say whenever I told them I was leaving America and moving to Paris to sit out the Trump nightmare.

I have always thought calling the French racist—especially when done by American Blacks—is a bit like the pot calling the kettle black. Whose racism is worse? White America’s or white Europe’s? This is the zero-sum race game we tend to play when looking at interactions between Blacks and whites in Europe. Can any predominantly white culture ever be free from racism directed against the people of color in its community? Europe is white, just like America. Notions of white superiority reign supreme in Europe, just as they do in America. Different white tribes. Same white sins.

But some tribes own their sins. Like the French. Though France was among the first European countries to get into slave trafficking in the early 1600s, it also became the first and only country to declare “slavery a crime against humanity” in 2001 when then-President Jacques Chirac named May 10th as a day to honor the memory of slaves and the abolition of French slavery in 1848. More than 500 years after the first transatlantic slave crossing that was to alter the fortunes of Blacks forever, the French were owning up. And France remains the only country to have called slavery what it is—a crime.

This past May marked the 20th anniversary of France denouncing slavery as a crime against humanity, but it also came one year after the vicious George Floyd killing which brought American racism to the attention of the whole world, leading to a renewed look at France’s own history with slavery and racism. As well as a current look at the country’s relationship with their people of color, Blacks living in France who are of African or Caribbean descent from countries once colonized by the French.

This racial reckoning was dramatized in a compelling social media quiz designed by personal coach Kathleen Dameron, a 40-year-long Black American expat in Paris and head of Sistah Circle, a consortium of Black women from the African diaspora who deal with issues ranging from self-empowerment to racial healing. Billed as “The 30-day Challenge,” the multiple-choice quiz featured a different question on French race history posted on the group’s Facebook page every day during the month of May. Questions covered topics from the slave rebellion in France’s colonial Martinique in 1678 to the French massacre of 45,000 Algerians in its North African colonial territory between May 8 and May 22, 1945.

I failed the quizzes miserably but was greatly educated in the process. I first learned that the barbarism of slavery practiced by the French in its Caribbean colonies rivaled anything American slavery was putting down and that the physical and mental atrocities committed by the French in the African countries they plundered transfigured the continent.

Charges of current-day racism on the part of the French directed against its Brown and Black people continue to persist in a country whose French people of color may be citizens, but practice Islam, not France’s Catholicism, or continue to speak their original native language, not French. Job discrimination. Housing discrimination. Discrimination, for instance, against those with African or Islamic names when reviewing applications for school admissions. These are a few of the reported human rights indignities leading to the French being called “racist too.”

I don’t dispute this, but I do know that French racism never comes close to matching the insidious racist acts that assault Black humanity in America every day: the continued killing of Blacks by the police; the blatant attempts to disenfranchise the Black vote; the intractable inability of America to acknowledge the reality its own history by opposing critical race discussions in schools, and the ongoing harassments by “Karens” everywhere questioning the right of Blacks to simply be.

The French do not roll like that. They will simply let you be. Not constantly reacting, often hostilely, to the color of your skin. Not shrinking from their own history. Not always in suspicious mode or white superior mode. No, the French possess a basic respect for a common humanity. Which is why they could denounce slavery as a gross inhumanity.

This is what thousands of Black American expats loved about the French when they began fleeing to Paris in the early 1900s, seeking refuge from spirit-crushing racism in the States. Josephine Baker, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, W.E.B. Du Bois, Nina Simone, Barbara Chase-Riboud, Beauford Delaney, Miles Davis, Grace Jones, Lenny Kravitz, to name but a few, are some of the Black creative artists and thinkers who have called Paris home briefly or permanently during the last 100 years.

The French have historically also liked Black Americans. They admired the courage of the Negro soldiers fighting in Europe during World War I who helped save the French republic even as they were denied freedoms in their native America. They loved the talent and energy of the early arriving Negro American artists and entertainers, recent descendants of a brutalized slave class not unlike the feudal class in France’s own pre-French Revolution days, who nevertheless managed to create brilliant art and exhibit great personal style.

I continue to admire and love the sensibility of a country that can “nation up” by acknowledging the sins of its past and trying to make amends. I love that in 2018 Emmanuel Macron, France’s president ordered the return of 28 pieces of Benin art stolen from the West African country during France’s colonial conquests. I love that just this past July, Macron awarded Rev. Jesse Jackson with the Legion d’Honneur, one of France’s highest honors, for what Macron called Jackson’s “a long walk towards emancipation and justice.” I love that Paris has a park named after Nelson Mandela, as well as two enormous iron sculptures in two other city parks depicting the broken chains of slavery.

This is also the country that has a plaque hanging in Paris’s famed Pantheon, its Roman-styled temple of heroes, with the name Toussaint Louverture inscribed on it, in honor of the Haitian military general whose forces defeated Napoleon’s army in 1803 when France tried to reinstate slavery in its former colony of Haiti. It was the only successful slave revolt in history, a pivot leading to the permanent abolition of slavery in the French colonies in 1848. Like I said, any country that honors the Black man whose army kicked the French army’s ass in a war—a war over slavery, no less–is fine with me. The French know how to show respect.

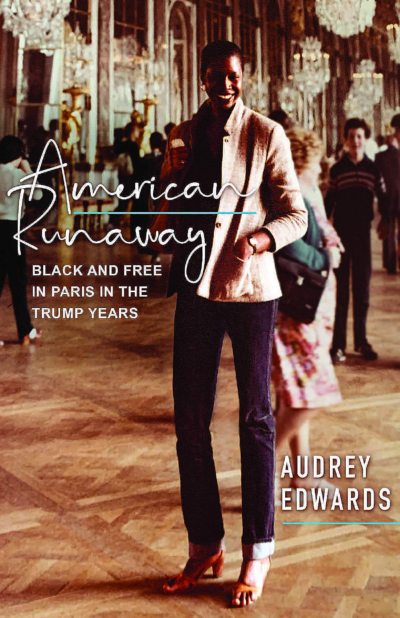

Audrey Edwards, a former editor and executive editor of Essence magazine is the author of AMERICAN RUNAWAY: Black and Free in Paris in the Trump Years, available at Americanrunaway.com or on Amazon.