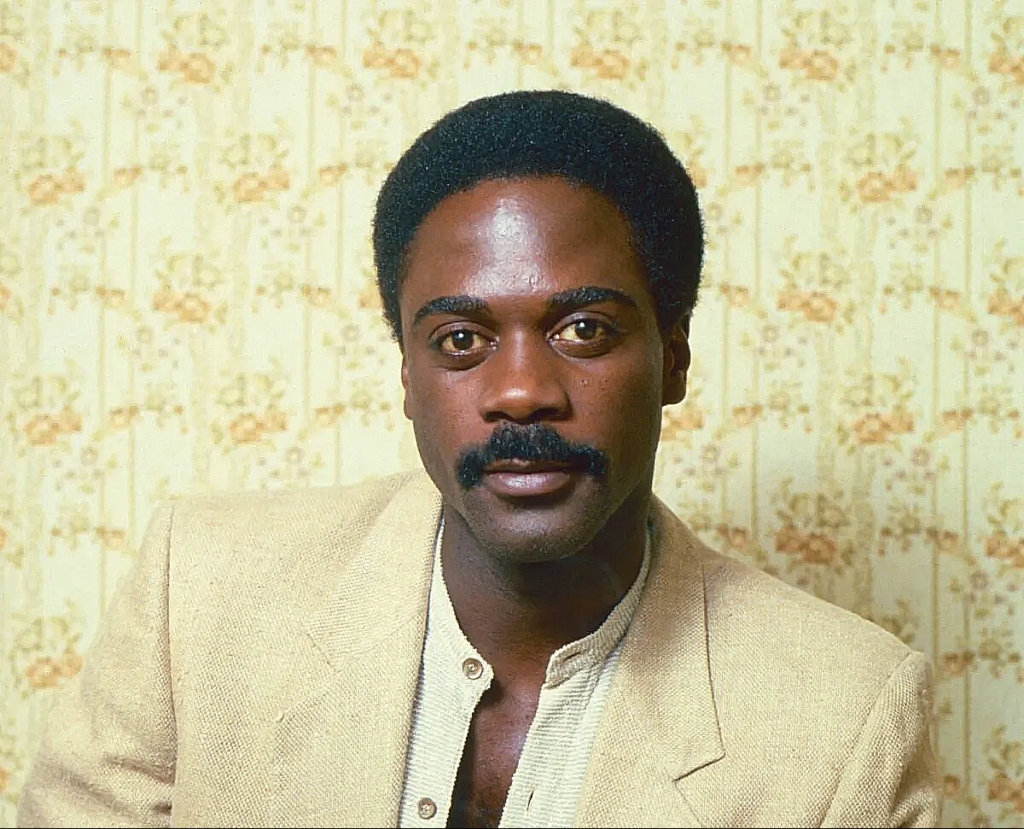

Dr. Roz, my sisterfriend, has exquisite taste in general, but when it comes to movies and TV shows, not so much (sorry Dr. Roz). Simply put, Dr. Roz adores those garden variety mindless cash-grabs, zero-budget disasters, and cinematic catastrophes! So, when I mentioned to my ride or die, that I was working on a feature about the late actor, Howard Rollins, she got excited. I became puzzled. What happened to her preference for brain-breaking films? Well, Dr. Roz’s love for everything Howard Rollins made me look at her in a new light. Maybe she does possess an inkling of good taste film-wise, after all, Howard Rollins’ work is at the top of her list.

Howard Rollins was born on October 17, 1950 in Baltimore, Maryland to parents Ruth, a domestic, and Howard, a steel worker. He was the youngest of four children. Rollins graduated from Northern High School in 1968, then attended Towson State College for two years.

In 1970, Rollins, then 20 years old, left college to appear in Our Street, a serial produced by the Maryland Center for Public Broadcasting. Fifty-six episodes were produced, depicting an African-American family’s continuing search for dignity and respect in West Baltimore. Our Street was syndicated to twenty other PBS stations, giving Rollins his first national exposure. Four years later, Rollins headed for the Big Apple, in search of his big break. He landed various theatrical jobs on and off-Broadway–We Interrupt this Program (1974), Medal of Honor Rag (1976), Shakespeare in the Park’s Measure For Measure (1976), and The Mighty Gents (1978).

Rollins finally landed his dream role in 1978 when he was cast as Andrew Young in the NBC-TV mini-series King opposite Paul Winfield. Apparently, casting directors thought Rollins was the ideal actor to portray Civil Rights figures. He was also hired to play George Haley, brother of Roots author Alex Haley, in the ABC mini-series Roots: The Next Generation (1979). Rollins was also cast as activist Medgar Evers in the PBS American Playhouse production of For Us The Living (1983). And, in the 1986 TV movie The Boy King, he played Martin Luther King, Sr., father of the slain Civil Rights leader.

By the time 1981 rolled around, Rollins was more than ready to make his big screen acting debut in the memorable classic, Ragtime. Rollins’ co-star was the great actor James Cagney who at age 82 had come out of retirement to appear in the film. Rollins was once quoted as saying how nervous he was to meet Cagney. “I was frightened to meet Mr. Cagney. I asked him how to die in front of the camera. He said, ‘Just die!’ It worked.” Rollins’ first-ever feature film performance in Ragtime earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor which is a rare occurrence in Hollywood. He was also nominated for two Golden Globes for Ragtime in 1982: Best Supporting Actor and New Star of the Year in a Motion Picture.

Despite the accolades, Rollins was not inundated with film offers. The only other film he appeared in was A Soldier’s Story (1984), directed by Norman Jewison who told People Magazine how he thought Rollins “had a quiet elegance and dignity.” The racial murder mystery had a stellar cast that included Denzel Washington, Robert Townsend and David Alan Grier. Rollins portrayed Captain Richard Davenport, a military investigator who was assigned to delve into the brutal murder of a World War II drill sergeant, brilliantly played by the late Adolph Caesar. The film received a cool reception at the box office.

Carroll O’Connor, who is best known for his role as Archie Bunker on the hit sitcom, All in the Family, was both the star and producer of the hit CBS drama, In The Heat Of The Night (1987). It was O’Connor who selected Rollins for the role of detective Virgil Tibbs. “I wanted Rollins from the start,” O’Connor told the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. The veteran actor was also quoted in a 1996 People Magazine interview, “I’ve worked with many talented actors, but never one more gifted.”

Problems soon developed on the set of In the Heat of the Night. Rollins was reportedly not comfortable with a few of the episodic racial issues. In 1988, Rollins began using crack cocaine along with alcohol, and his troubles became quickly known. The series was set in Louisiana where he was arrested on charges of DWI, speeding, and possession of cocaine. The arresting officer at the time stated that the two bags of cocaine he found on Rollins was in the smoke-able lump form known as crack. He tried rehab in 1990, but soon his drug and drinking problems overwhelmed him.

Rollins’ addiction problem eventually affected his work on the set; he’d either arrive late or failed to show up. He was again arrested in Georgia on three occasions in 1992 and 1993 for driving under the influence. The last arrest resulted in a 70-day jail sentence. Rollins’ drug issues got him placed on a leave of absence from the show in 1993 and despite his popularity, he was replaced by actor Carl Weathers. Following a stint in rehab, he returned as a guest star for three episodes in season seven. In an August 1993 interview with Jet magazine, Rollins discussed his recent brushes with the law. “I now have found other ways to try to make my situation work. I don’t regret anything I’ve done in my life because they’ve brought me here and I’ve become a better actor based on those things,” he said.

In 1995, Rollins appeared on Fox’s New York Undercover as a reverend. “He was a treat to work with,” NYU producer Don Kurt told People Magazine. “He’d turned his life around.” Later in 1995, Rollins was cast as a recovering alcoholic in Drunks, the film adaptation of the award-winning play about addiction. Rollins’ monologue on the destructive effects of substance abuse was eerily autobiographical and extremely poignant. Sadly, Drunks would be Rollins’ last film.

Rumors began to surface about Rollins being a homosexual. It was reported how the actor frequented gay clubs in New York, LA and San Francisco. He would often go clubbing with fellow gay actors, Raymond St. Jacques and Paul Winfield. But Rollins kept his sexuality under wraps. There were also whispers about Rollins being a cross-dresser. In the 90s, being openly gay could be a career-breaker, especially if vying for romantic leads. The stigma of AIDS was also at its peak.

In the fall of 1996, Rollins was diagnosed with AIDS. Six weeks later, he died at a hospital in New York City. He was only 46 years old. It was reported at the time that Rollins had passed from lymphatic cancer. It was, however, later revealed by his family that the death was AIDS-related.

On October 25, 2006, a wax statue of Rollins was unveiled at the Senator Theatre in his hometown of Baltimore. The statue is now at Baltimore’s National Great Blacks in Wax Museum.