“What American literature decidedly needs at this moment is color, music, gusto, the free expression of gay or desperate moods…. If the Negroes are not in a position to contribute these items, I do not know what Americans are.”

So passionately declared Carl Van Doren, the white editor of Century literary magazine at a 1924 assembly of leading Black writers and white publishers. And that is precisely what was unleashed.

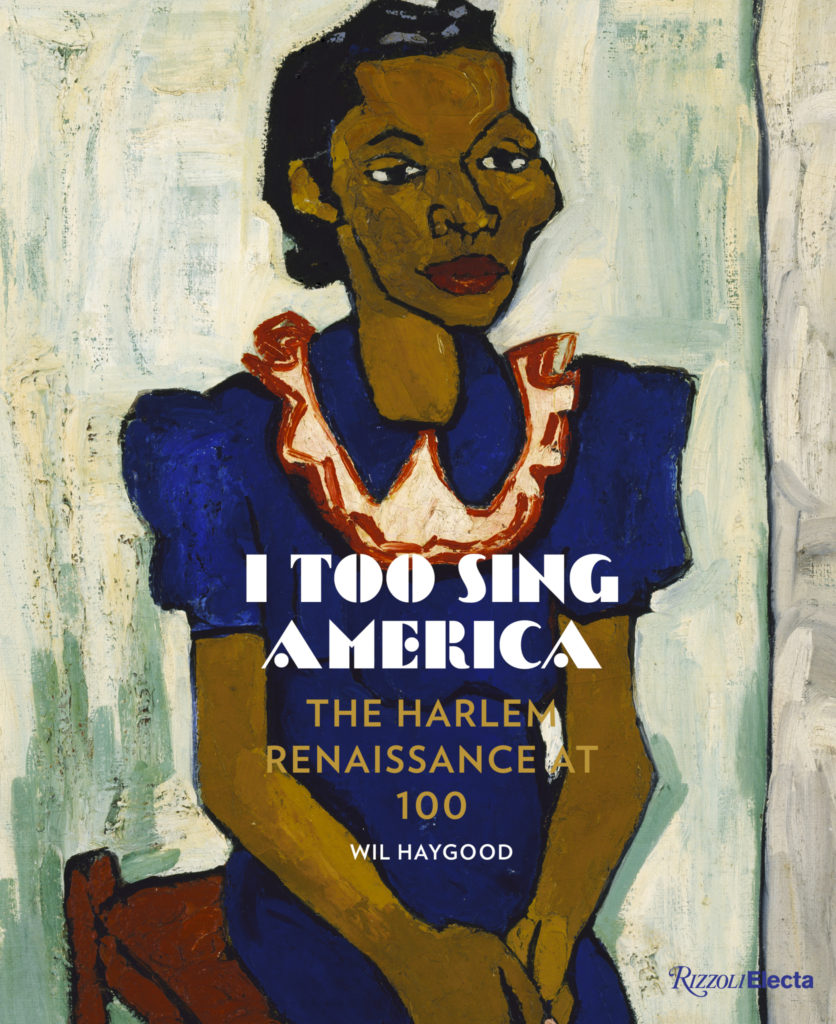

I Too Sing America: The Harlem Renaissance At 100 while both an engaging history lesson and an art catalog, is a labor of love by the prominent Black writer Wil Haygood. He has already contributed many great biographies of famous Black Americans in history. Some people he has written about earlier like Congressman Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., dwells with his father, the senior Powell, in an entire chapter in this present tome.

Wil Haygood may best be known for penning the book, The Butler, an amazing story of Eugene Allen, a Black butler who served in the White House for eight presidents. This retired hero lived to see the election of our nation’s first Black president, Barack Obama. And Haygood’s celebrated book became the basis of a major motion picture with a star-studded cast.

So the Columbus Museum of Art (CMA) chose no lightweight when they wanted to develop a book to accompany their exhibit, “Harlem Renaissance at 100.” And I, as one of many, applaud their choice, because as his name implies, Haygood delivered the goods.

As Nannette V. Maciejunes, Executive Director of the CMA writes, “The collaborative spirit of the Harlem Renaissance is reflected in I too Sing America, which illuminates the cross-disciplinary nature of artistic practices through paintings, prints, photographs, sculpture, books, graphic design, music, film, and contemporary documents and ephemera.” Maciejunes notes that for this companion book, Haygood chose from objects showcased in the exhibition with help from members of the CMA curatorial staff.

My only aside is…Why was this exhibit and book created and presented in Columbus, Ohio, and not in the Village of Harlem, NYC, where the Renaissance started and largely took place?

That question notwithstanding, I like what I see on the book’s pages. From reading this informative work, I learned that the genesis of the Harlem Renaissance was from World War I, when segregated Black regiments were finally allowed to fight, and serve in, among other places, France. There, they encountered a racially tolerant society that was eager to learn about Black arts and culture.

Emboldened by the good treatment they received, the Black GI’s returned to the States expecting to be dealt with more fairly, since they had so bravely fought. But what greeted them on these shores was more lynchings, and “same as before” treatment by white America.

The “New Negro,” a term made famous by the Harlem Renaissance, influential Black writer and philosopher, Alain Locke, who demanded equality. Black intellectuals felt that a more effective way to present themselves on par with whites was through the arts.

As a Black enclave, Harlem was destined to be the epicenter of this talent, though the movement reverberated to other parts of the country. Black artists, writers, and political figures migrated to Harlem. One amazing poet, Countee Cullen, was my father’s middle school English teacher!

Although the Harlem Renaissance simmered out in the mid-1930s due to the economic stagnation of the Great Depression, the effects of that “magical” era are still present. In 2018, there is a myriad of Black artistic talent. But the great demand is for work by select contemporary Black artists, both alive, like Kehinde Wiley; and dead, like Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose paintings sell for millions.

Let’s return to our book. Greats such as the intellectual William W.E.B. Du Bois, the famed poet Langston Hughes, folk-writer Zora Neale Hurston, James Van Der Zee, with his achingly beautiful and artistic photographs, are all showcased here.

In addition, we are also introduced in the book to artists I hadn’t known before such as painter Aaron Douglas, sculptors Richmond Barthe and Augusta Savage. View the work of white artists who were part of the movement, such as German-born painter Winold Reiss, whose portraits of everyday Harlemites is a showstopper to this very day.

At the time, Reiss’ portraits “were a commercial failure,” as his critics included both Blacks and whites. One viewer at Harlem’s, Countee Cullen Library’s exhibition said of one portrait, Type Study II, which featured beautiful dark-hued teachers with striking features, the women “would have frightened him had he encountered them on the street.” Others were bothered that Reiss depicted darker-skinned Blacks, as if they aren’t beautiful, as well, so they shouldn’t exist in the world of art. And that Weiss, as a white person, should not have been involved. But not everyone felt this way, including the Harlem Renaissance artists.

As sculptor Sargent Claude Johnson eloquently articulated in 1935 in the San Francisco Chronicle, “It is the pure American Negro I am concerned with, aiming to show the natural beauty and dignity in that characteristic lip and that characteristic hair, bearing, and manner; and I wish to show that beauty not so much to the white man as to the Negro himself.”

In 2018, 100 years after the start of the Harlem Renaissance, I wonder how far we, as Black Americans, have come with appreciating our African beauty. Witness world-famous Black singers such as Janet Jackson“lighten up” or as she, and the rest of her talented and beautiful as God made them, family, get nose jobs and other plastic surgeries, in an effort to look more Caucasian, it would appear. And her famed brother, my eternal love, Michael Jackson, notwithstanding his signature song went from Black to white. I, for one, grew up constantly being called “ugly,” because of my acne and sub-Saharan Bantu features. That is why, when I met a young, handsome, Michael Jackson in 1970, I felt too unworthy and repulsive to shake his hand or even look into his beautiful eyes. Did he feel the same way about me, about himself?

We must overturn our understandable internalization of five centuries of inferiority dictated by white America, which are still coming at us. It’s time for us as Black people in America and around the planet to fully recognize our amazing wit, talent, and loveliness. We are a people who survived chattel slavery, sharecropping, and rampant, lingering discrimination, to achieve great success. Haygood’s book is a testament of the wonderful things we, as a people, have, and continue to accomplish.

I too Sing America is a rich embodiment of a great cultural, artistic and intellectual period in America’s history. There are lots and lots of beautiful art in the book as well. The book would also be an affordable and memorable Christmas or birthday gift for someone you love. I hope you buy it for yourself as well. Don’t just treat it as a coffee table enhancement, but read and find out why James Brown was so on point in 1968 when he proclaimed, “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud!’

Notes: Haygood did a fine job of research, as evidenced by the extensive Notes and Index at the end of the book. This literary work is accessible to the lay reader, although you may have to visit a good dictionary to understand some terms. Most artistic reproductions are of high quality, though a few, including on the back cover, appear grainy or blurred. This effect may be due to the age and texture of the original work. End pages feature a lively illustrated “Night Club Map of Harlem” by E. Simms Campbell, engraved in 1932.

I Too Sing America: The Harlem Renaissance At 100 ($55) is published by RizzoliElecta Publications and can be purchased at book sellers everywhere including Amazon.com