Talk of the COVID-19 and its variants appear to be the focus of practically every conversation these days especially in our community. There seems to be a lingering mistrust of the medical system regarding the COVID-19 vaccine.

Many folks in our community are hesitant to pull the trigger on receiving the coronavirus vaccine. They are finding it difficult to separate the painful memory of the decades-long Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment from their personal deliberations over whether to vaccinate or not. That history is now returning to haunt the U.S. medical establishment.

The pain, hesitation, and mistrust are rooted in history. Trust is critical to health.

There is a lot of misinformation about the infamous study that requires clarification.

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male was the proper name of the experiment that began in 1932. The project included blood tests, x-rays, spinal taps, and autopsies of the participants. At the time there was no cure for syphilis which is a sexually transmitted disease.

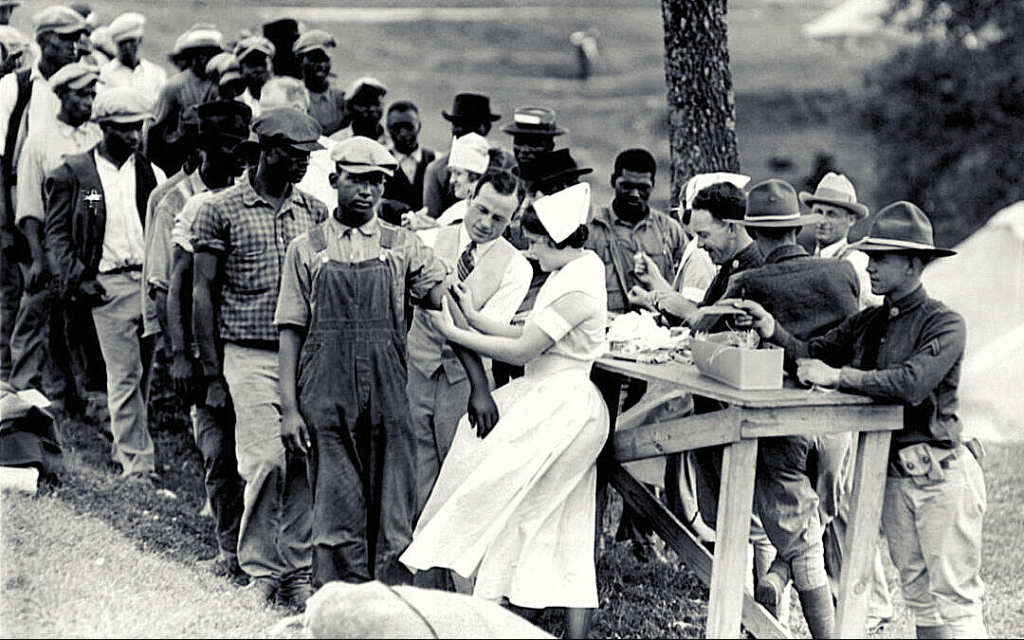

Physicians from the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS), who were conducting the syphilis study, recruited about 600 Black men, mostly sharecroppers in Macon County, Alabama to take part in a project aimed at observing the natural progression of the disease. A total of 399 men had latent syphilis and a control group of 201 others were free of the disease. At the time, 35% of the area’s population was infected with syphilis.

The sharecroppers who were uneducated and between the ages of 25 and 60, were unaware of the study’s true intentions. The experiment was conducted without informed consent. The men were told that the treatment would last six months and promised free healthcare for their ‘bad blood condition,’ a term that translated into anemia, syphilis, fatigue, and other health issues.

A year after the study began, researchers decided to continue their project long-term. They began giving all patients ineffective medicines like aspirin and mineral supplements to further their belief that they were being treated.

As time progressed, some patients stopped going to their appointments altogether, so a nurse was hired to transport them to and from their medical visits. The researchers also lured the patients by providing hot meals, medicine deliveries, and paying for any funeral costs.

USPHS worked diligently to block any of their patients from receiving outside medical assistance that could have saved their lives. In 1934, USPHS provided doctors in Macon County with lists of their subjects and asked the medical professionals not to treat them. In 1940, the researchers did the same with the Alabama Health Department.

In 1941, many of the study participants were drafted and had their syphilis uncovered by the entrance medical exam, so the researchers had the men removed from the army, rather than let their syphilis be treated. The research was also eventually moved from Macon County to the Tuskegee Institute, a historically Black college.

By 1947, penicillin was the gold standard for treating syphilis. The medicine penicillin is (and was) recommended for all stages of syphilis and could have stopped the disease’s progression in the patients.

Researchers provided no effective care as the men died, went blind, insane, or experienced other severe health problems due to their untreated syphilis.

The Centers for Disease Control (which had taken over from the USPHS in controlling the study) actively decided to continue the study as late as 1969. It wasn’t until a whistleblower, Peter Buxtun, leaked information about the study to The New York Times and the paper published it on the front page on November 16, 1972, that the Tuskegee study finally ended. By this time only 74 of the test subjects were still alive. 128 patients had died from syphilis or its complications, 40 of their wives had been infected, and 19 of their children had acquired congenital syphilis.

After the lid was blown off the experiment, there was mass public outrage, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) launched a class-action lawsuit against the USPHS. After a two-year battle, the lawsuit was settled for 10 million dollars. The agreement that was reached would pay the medical treatments of all surviving participants and infected family members, the last of whom died in 2009.

Sadly, to this very day, not one soul has yet to be prosecuted for their heinous role in dooming 399 Black men to syphilis.

The best way to learn from the atrocities of the past is to change our present. Skepticism should always be employed. However, it is exceedingly dangerous when skepticism in our community becomes so intransigent and intellectually slipshod that some of our leaders and activists encourage people not to do the things that can save their lives and that of their neighbors.