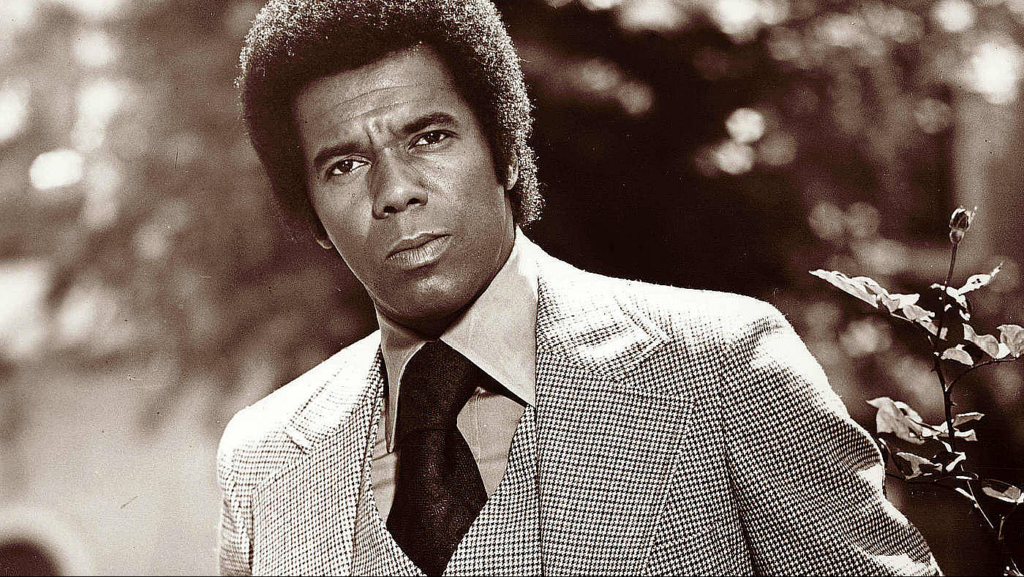

“Get me Robert Hooks!” was a demand frequently uttered by top theatrical producers throughout the 60s. Robert Hooks is a name that has been synonymous with acting perfection for over 50 years.

The cultural architect who has never been driven by accolades has an awards cupboard, both metaphorically and literally, that is very much full. He has performed in over 65 plays, eight of them Broadway shows and has over 100 TV and film credits. A standout accolade is an Emmy Award for producing Voices of Our People: In Celebration of Black Poetry on PBS (1982). Robert has also received numerous Lifetime Achievement Awards, has been inducted into The Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, and even had Robert Hooks days proclaimed in various cities. Over the years, Robert has directed his passion for the arts towards changing the landscape of Black theater and Black Hollywood as well.

Throughout the years, Robert has used his talents to obtain opportunities for rising Black artists. As a matter of fact, he has been touted as an intergenerational visionary and institution builder. An actor, producer, director, activist, philanthropist, many are unaware of the magnitude of Robert’s commitment and impact in the Black community.

Simply put…Robert broke down the wall for other Black artists, many of whom would not otherwise be working in the mainstream.

Robert is also a man of firsts. He was the first Black performer to appear in a network drama, NYPD, in 1967. He was the first Black New York producer to produce a Black play with Black backing for Douglas Turner Ward’s double-billed plays Happy Ending and Day of Absence.

In 1967, Robert co-founded and was the principal driving force for the groundbreaking African American theater troupe, the Negro Ensemble Company (NEC). The organization’s other co-founders were playwright Douglas Turner Ward and theater manager Gerald S. Krone. The creative also founded the DC Black Repertory Company and the Los Angeles NEC.

At the very core of the Black theater movement, Robert could be found launching the careers of countless actors, directors, producers, writers, choreographers, dancers, and administrators who ALL came through NEC. The Negro Ensemble Company’s list of alumni is a who’s who of Black America in the arts: Denzel Washington, Cicely Tyson, Angela Bassett, Samuel L. Jackson, Alfre Woodard, Phylicia Rashad, Debbie Allen, James Earl Jones, Roscoe Lee Browne, Esther Rolle, Roxie Roker, Adolph Caesar, Garrett Morris, S. Epatha Merkerson, Rosalind Cash, Antonio Fargas, Lawrence Fishburne, Sherman Hemsley, Lou Gossett, Jr., Debbie Morgan, Delroy Lindo, Glynn Turman, and Billy Dee Williams.

Robert also passed down his acting gene to his sons Kevin and Eric. Kevin is a distinguished film/TV director who cast his dad in two of his films, Passenger 57 (’92) and Fled (’96).

At 83, Robert Hooks is indeed our national treasure, a true definition of a mega-trailblazer. And truth be told, Robert is incredibly humble; he is a man who has learned to deflate pretentiousness and who takes genuine delight in the successes of his peers. “Life is more than me. Life is more than you. This is what I’ve always taught my actors. It’s not about you. You fall in love with yourself, and that’s good because you need that to be an actor or an artist. You need to love and to know yourself. But then–get over yourself!”

Robert Hooks has had quite a fascinating life’s journey, and we at 50BOLD are honored to chat with him about it.

50BOLD: You were born in DC and are the youngest of five children. Your father passed when you were two-years-old. You’ve stated that your siblings played a significant role in your upbringing. How would you describe your childhood growing up?

Robert: First of all, my four siblings took care of me like you would not believe. I was the baby of the group. We lived in a flat house on Newport Place, and all slept in the same bed. They made me the person I’ve become.

50BOLD: You attended segregated schools in DC, how has this shaped your outlook on life?

Robert: I was born and raised in Washington, DC, and attended segregated elementary, junior high, and part of high school. Do you know the advantage of going to an all-Black school? The Black teachers would make sure their students understood what being Black is all about. I learned more about our history in elementary and junior high school than I’ve ever learned for the rest of my life. The teachers who could not teach in other schools made sure that my classmates and I knew our history. Roberta Flack was my classmate in elementary school; we were buddies.

When I went to West Philadelphia High School, it was wonderful; it was a melting pot: Italians, Asians, whites, and Blacks. It was culture shock yet, a fantastic experience.

50BOLD: So, you moved from Philadelphia to New York City in 1959 to pursue an acting career, and you debuted as Bobby Dean Hooks in the play A Raisin in the Sun. But after actor Roscoe Lee Browne saw you in the Dutchman play, he convinced you to change your name from Bobby Dean to Robert. Why did you follow his advice?

Robert: Well, Roscoe was brilliant and a dear friend. He was probably the most intellectual actor I’ve ever met. Roscoe Lee Browne was a mentor. I was doing Dutchman, and he came to see me in the play. The night before, Langston Hughes came to see the play because he was writing an article about Black actors on Off-Broadway for the NY Post.

The night Roscoe came to see the play, we went to Chumley’s restaurant afterward, where I’d meet friends for dinner and drinks after a show. Roscoe sat across from me and said, (impersonating Roscoe’s erudite diction), “Robert, after tonight, you are going to have to change your name to just Robert. You are no longer Bobby Dean. We already have a Billy Dee, and I saw a Robert on that stage tonight.” And that was it. I went to Actor’s Equity and changed my name legally from Bobby Dean Hooks to Robert Hooks.

50BOLD: So, Roscoe Lee Brown anointed you?

Robert: Exactly.

50BOLD: When I interviewed Antonio Fargas for 50BOLD, he mentioned how he had gotten his start in The Group Theatre Workshop that transformed into the Negro Ensemble Company. Fargas said he has the utmost respect for you, and even to this day, considers you his mentor.

Robert: I am his mentor and dear friend. There are a lot of actors, writers, and directors in this industry who will tell you the same thing. I took a group of kids off the streets of New York who were interested in becoming entertainers, artists. The play that I was doing at the time was Leroi Jones’ Dutchman. It was a big, big hit. I was asked to come to the Chelsea Civil Rights Council to talk about the importance of theater. We were in the midst of the Civil Rights era at that point. At the time, there were drugs, gangs, and all kinds of happenings in the streets. The audience was packed. By that point, I had already done three Broadway plays.

When I was leaving the building, these kids were following me; Antonio was one of them. Daphne Maxwell Reid and Hattie Winston were also there. I found myself holding court with about 15 young kids from the neighborhood. They were all asking questions. I said, ‘Look, I live across the street. Monday night is the Off-Broadway actor’s night off. Come over to my house at 6’o’clock next Monday and let’s finish this conversation.’ Well, Karen, next Monday, there must have been 30 kids at my door!

50BOLD: Whaaat!

Robert: As many as 30 kids came into my living room, and this is how the workshop started. We hadn’t even given it a name yet. I thought, ‘Damn, these young kids really and truly are enthusiastic. They want to do this.’

The workshop grew and grew. Writer, producer, and actress Dr. Barbara Ann Teer was a dear friend. I brought in Barbara Ann to help me work with these kids and decided to call the gathering The Group Theatre Workshop.

We met every Monday for poetry and teaching. The kids and I got our crowbars, hammers, and knocked out the wall in my apartment because the landlord never came around. We built a stage in my living room, and there were 22 seats for the audience. Barbara Ann eventually went to Harlem and started her company, the National Black Theatre.

Once we got going, we had daily sessions. I had Lonne Elder III, Douglas Turner Ward, Barbara Ann, and Ron Mack come and teach. Kids who were 15, 16, 17 years old were in and out of my apartment. I would get complaints from neighbors. The neighbors wanted to know what was happening. We had about 40 kids in our group and were doing excellent work. We had put together a lot of Gwendolyn Brooks poetry readings, and We Real Cool was our go-to poem from her book The Bean Eaters.

Barbara Ann and I decided to put together a showcase for our neighborhood to show them what we were doing. I asked the great playwright Edward Albee to give us the Cherry Lane Theater on Monday night. When we held our showcase, it was standing room only. I asked Douglas Turner Ward to let me do his play Happy Ending to closeout my showcase. I directed Hattie Winston and James Long in Happy Ending; they were my top actors in the young group. It was a fantastic evening.

Jerry Tallmer, one of the top theater critics for the NY Post was at the showcase; I was unaware of this. The next morning the NY Post published a glowing review of Robert Hooks and his Group Theatre Workshop. Tallmer ended his review by praising the Happy Ending play. I told Doug, ‘Do you see this? It was done with four young kids. Let me produce your double-bill plays Happy Ending and Day of Absence.’ At the time, Juanita Poitier, Sidney’s ex-wife said, “I know where you can go get some Black money. Clarence Avant and Al Bell just started the Stax Record company. Go ask them for the money to produce the plays.” I called Avant and Bell, and they invited me up to Harlem to Frank’s Steakhouse, a famous restaurant on 125th St at the time.

When I entered the restaurant, it was packed with all white people, Clarence, Al, and I. I brought both the Happy Ending and Day of Absence plays with me. I began reading and acting out the roles in the plays. The people in the restaurant were cracking up. I performed as if I was in a theater.

Clarence and Al eventually stopped me and asked, “How much money do you need?” My budget was $35,000 for the production of the plays. They told me to come to their office the next day, and they would give me all of it. They gave me a check for $35,000; I produced Happy Ending, and Day of Absence myself with Black money. I was the first Black producer who produced plays in New York City with all Black money!

We produced Ward’s Happy Ending, and Day of Absence. Now, mind you, I was doing Dutchman, and it was a big hit for Leroi Jones. Now, I had plays that I was going to produce and act in, too by Douglas Turner Ward.

The plays were a smash hit. They bumped Leroi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka), who was the playwright of the day. By the time we produced Happy Ending and Day of Absence, they were so brilliant that Doug became the playwright of that particular time. After the play had been running for a while, Douglas was approached by The New York Times and asked if he would write an article for their Sunday drama section about Black theater in America. The year was 1966. Doug wrote the article for The New York Times called American Theater: For Whites Only? It was a scathing account of what theater was really all about in this country. The producers and theater-goers in New York City were all up-in-arms about the article.

OK, so the double-bill plays are going strong. Douglas, Lonne, Barbara Ann, and I are in the plays. The Ford Foundation got wind of the article and called us. At the time, foundations were trying to help communities and Black artists. We met with foundation heads and were advised to get a proposal together. Jerry Krone, who was white and the third member of our triumvirate, was a brilliant numbers man.

Our proposal was drawn up on white paper tablecloths at a watering hole for actors in the East Village. We mapped out three years for our company. We took our proposal to the Ford Foundation and received $1.5 million; today, the figure would come to about $15 million. The monies given to us by the foundation was for three-years and this is how the Negro Ensemble Company got started.

50BOLD: What an amazing story! So, the NEC began in 1967?

Robert: Yes, 1967! When we started the Negro Ensemble Company, the name ensemble had to be in the title because I was so moved by the Berliner Ensemble Company in then, East Germany. Now, the word “Negro” offended a lot of Black power people. We wanted Negro in our title because The Harlem Renaissance was the heart of Black theater, where it all began. We wanted to pay homage to the renaissance, and they were all Negroes.

50BOLD: After Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968, you started a DC Black Repertory Company, correct?

Robert: That’s right. Dr. King and I were friends. He was a mentor. He loved what was happening in theater. As a matter of fact, when I was doing The Blacks, another great play, he and Coretta came to see a performance. The Civil Rights movement with CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee), SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference), and NAACP – all of these organizations were doing benefits to raise money for the work they were doing down south.

We were involved in the Civil Rights Movement at Jimmy Baldwin’s (James Baldwin) house, Harry Belafonte’s house, Lena Horne’s house; we would all help raise money for the cause. We would collect checks from the patrons who attended benefits—Diana Sands, Lonne Elder, Ed Hall, all of them are gone now, unfortunately. We’d go to Small’s Paradise in Harlem and read poetry or excerpts from Jimmy’s books to help raise money for the Civil Rights Movement.

50BOLD: I had no idea all of this was going on.

Robert: Yeah, a lot of people don’t know the history of it all. We were called The Young Turks. There were six of us. After doing the Broadway shows, we would attend benefits and perform readings.

50BOLD: You have been such a driving force in theater. You have opened doors and nurtured countless Black artists—actors, dancers, writers, directors, administrators. Your dedication/commitment to the Black arts is just praiseworthy. You have accomplished so much, yet, you remain humble.

Robert: Well, let me tell you, my autobiography is in the works. The title of my autobiography is More than Myself: At the Crossroads of Culture, Politics and the Civil Rights Movement. I’m paraphrasing.

Life is more than me. Life is more than you. This is what I have always taught my actors. It’s not about you! You fall in love with yourself which is good because you need to do this to be an artist. You need to love yourself, know yourself, but then–get over yourself!

50BOLD: Yesss! I love it! So many artists should follow this school of thought!

Robert: So right, and that’s the problem! You’ve got all these Black actors and producers making millions and millions of dollars but not giving anything back! They’ll write a check for a church or the Boys and Girls Clubs but what about that theatrical group on the corner trying to start a company? How about helping them? How about putting your name on a theatrical building?

50BOLD: Absolutely!

Robert: The multi-million-dollar Black celebrities, I’m not going to call out any names, but you know who they are. You try to get them on the phone; they won’t answer my calls, Karen. These are the very same people whom I had created opportunities for.

50BOLD: Are you serious?

Robert: They won’t answer my freakin’ phone calls because they suspect I’m going to ask them for something. And I am going to ask which is why I call them. I state, how I need them to lend their name to a coalition to make things better for the Black community. They don’t answer my phone calls. They don’t call me back….

50BOLD: It just saddens me to think about it.

Robert: It’s true, very true. They are in a bubble. White celebrities are in bubbles but manage to give back. Some of the Black folks give back. Oprah gives back. The easiest thing to do, if you’ve got it, is to give back.

We don’t have that many Black theater companies in the community. I created The Group Theatre Workshop so that young Black artists could come and be sincere about what they wanted to do.

50BOLD: Is there a role you regretted doing or not doing?

Robert: I’ve done so many great roles. All the roles I have taken on have been dignified. Fortunately, I could choose my roles; a lot of actors can’t. If they go and audition for a role and they get it, that’s it. They have to do that role. I didn’t have to do that.

I did A Raisin in the Sun and didn’t have to audition for it. My first movie was Otto Preminger’s Hurry Sundown. Otto came to see one of my Broadway plays and called me at Sardi’s on opening night. Performers would go to Sardi’s, a popular restaurant in the theater district, and wait for reviews. I remember going to Sardi’s and seeing the owner Vincent Sardi bring phones over to people’s tables.

Anyway, Vincent walked over to my table with a phone after I did this play, and he handed it to me. I thought he was kidding me. He said, “Somebody wants to talk to you.” I said, ‘Hello.’ And I get this voice, (in a German-sounding accent) “Is this Robert, Robert Hooks? This is Otto Preminger.” I thought somebody was playing with me. He said, “I would like you to come to my office tomorrow. I would like to talk to you about doing my movie with Diahann Carroll, Jane Fonda, and Michael Caine.” He’s talking to me and I’m almost crying. That’s how I got my first big movie.

50BOLD: Your body of work is insane!

Robert: I’m just talking now about Broadway. I’ve done eight Broadway shows. You will never meet an actor who has done eight Broadway plays. I was doing play after play; Tennessee Williams…. I was being directed by the greats. When a role came up, producers would say, “Can we get Robert Hooks for this?” I was very fortunate. I was the busiest actor in New York City; this is just how it went down for me.

50BOLD: What are your thoughts on Tyler Perry? You know he has the Tyler Perry Studios in Atlanta, one of the largest film production studios in the nation. Perry has established himself as the first African American to outright own a major film studio. All of his soundstages are named after celebrities you helped in the industry. I have to ask, then where is the Robert Hooks soundstage?

Robert: (laughs) Well, let me just say this about Tyler. I don’t know him personally. He is, however, a hero of mine. He has done something that no other Black producer has ever done. I am happy for his success and anxious to see the studio when I get that way. I love the fact he has named stages after actors, and he certainly doesn’t have to name one after me. I am very, very proud of that young man. Nobody has ever done what he has done. Nobody!

Tyler Perry, this man could have done what these other performers do. They just run to the bank, buy their houses, car, planes, and shit — forgive me for my language. Tyler is producing stuff, and this is what’s important.

50BOLD: (laughs) You have always had leading-man-good-looks, Fine is fine with you, isn’t that right?

Robert: Well, I appreciate the compliment, and my wife will appreciate it too! I take care of myself, always have. When I began acting, a very good friend of mine who was also in A Raisin in the Sun told me, “You are a leading man, this is who you are. Take care of yourself as a leading man.” All of my career, I’ve been a leading man who takes care of himself. I make sure I look the way a leading man looks wherever he goes.

I retired from acting about 15 years ago. I retired because I love acting, and they weren’t giving me the roles that I deserved. My agent would send me a script, and I would call him back and say, “I can’t do this role, it’s a step backward.” In our line of work, we should move up, not move back.

I just decided the roles were going to Samuel L. Jackson, Morgan Freeman, James Earl Jones, but they weren’t coming to me. I’m glad I retired because now I’m doing all kinds of wonderful things.

50BOLD: I was on YouTube watching the TV mini-series Sophisticated Gents; you appeared in that film in 1981. Watching it again, just warmed my heart. All of that wonderful Black talent!

Robert: I know! Wasn’t it wonderful?

50BOLD: Sadly, Ron O’Neal, Dick Anthony Williams, Paul Winfield, Thalmus Rasulala, Bernie Casey, Raymond St. Jacques — all have passed. And the female actresses who have passed– Ja’Net DuBois, Rosalind Cash, Beah Richards, and Janet MacLachlan. Thankfully, Denise Nicholas and Alfre Woodard are still with us! What was it like to be a part of such an extraordinary mini-series?

Robert: It was historic! You just didn’t get that many brilliant actors together at one time. Everyone had their own brilliance going for them. I had so much fun working with my comrades. Sophisticated Gents was a once in a lifetime historic event. I am so happy I was part of the cast.

50BOLD: Now, this is called the Rapid Round, I’m going to name three topics, and you can respond, however, you please. Here we go:

Donald Trump–The worst president in the history of the world! A maniac!

The Black Lives Matter Movement–I’m certainly happy this necessary movement has finally caught the world’s attention.

COVID-19–The worst thing that has ever happened to this country for sure. It didn’t need to be as bad as it is. It could have been snuffed out earlier. Donald Trump played with it politically, claiming it was going to disappear. Hundreds of thousands of people have died. Trump is a con man. Remember, Jim Jones? Trump’s cult is made up of those followers whom Hillary called deplorables; well, she was right. Trump’s followers are like Jim Jones’ followers, you know, the people who drank the Kool-Aid.

50BOLD: Tell us something people don’t know about you?

Robert: A lot of people don’t know how much I love to garden. When I lived in New York City, I had a garden on my balcony. When I moved out to California, I lived near Jim Brown up on Sunset Plaza Drive, where the houses are on stilts. I had a garden beneath my house. Now, I am in Toluca Lake, and I’ve got all the space I need. I have citrus trees, guava, tangerines, peaches, I have all kinds of stuff.

50BOLD: You’ve been married to your third wife, Lorrie, for 12 years; where did you two meet?

Robert: I met Lorrie Marlow when I was at the Negro Ensemble Company. Our company photographer, Bert Andrews would shoot all of our plays. He would always have an assistant with him. One day he walked in and was accompanied by this beautiful woman with great legs and a great ass, oh, excuse me. (laughter)

I said, “Bert, damn!” Lorrie was like 18 when I first met her. I was married and then, married again. Throughout the years, I would see Lorrie. I then moved to Los Angeles, and one day, I was at an event honoring Woody King, Jr. (director and producer), and there was Lorrie; I was divorced from my second wife at the time. When I saw her, I thought, ‘Now is the time!’

50BOLD: You have an interesting marriage.

Robert: Yes, it’s called a LAT relationship–Living Apart Together. This is how it works. Lorrie always had a condo over in West Hollywood. I have a house in Toluca Lake. When we were dating, she would come over on Friday, and we would spend the weekend swinging from the chandelier. (laughs)

So, when we decided to get married, I love Lorrie, so I’m ready to live 24/7 with her. She said, “No, no, no, no! I’ll keep my condo, and we won’t change.” So, Lorrie is here on Friday through Monday and then goes back on Tuesday to West Hollywood. It is fantastic!

The guys I grew up with who are in the industry don’t understand my arrangement with Lorrie. When I explain to them that she’s only here three nights, four days, and then, she’s back on the other side of town. They go, “Oh, my God, damn! I sure wish I could have a LAT relationship.” I say to them, ‘My friend, you couldn’t handle a LAT relationship because there’s another LAT that goes with it–Love and Trust. If you don’t have one, then you can’t do the other.’

50BOLD: Mr. Hooks, how would you like to be remembered?

Robert: I would like to be remembered as someone who cared for others. If I didn’t care for others, Denzel Washington wouldn’t have an Academy Award, Charles Fuller wouldn’t have a Pulitzer Prize, and I can go down the list of all of the actors who came out of the NEC!

50BOLD: When you get to the gates of heaven, what will God say to you?

Robert: He’ll say, “Robert, welcome! Now, here’s a script, go produce a play!”